This is a marvel of a film in many ways, for its extreme contrasts and almost paradox nature of joining utter horror tragedy with the idylls of paradise. It's a story of children written for children, but the film actually turns it almost into a horror feature, as the screaming child in the nights would give anyone compulsory nightmares, especially since no explanation is provided. Adding to the gloomy horror nature of a Dickens nightmare at its worst is Gladys Cooper as the totally cold-blooded aunt who is worse than a death skull in her insensitivity, and of course Herbert Marshall as the uncle, who for once has the opportunity for a different character than a gentleman. The tantrums are not those of his forcibly crippled son but of his own, which he projects on the world around him and especially on his only son, in a morbid effort to turn him into the same guilt complex martyr as himself. The scenes with the children are terrific, but the great trick is the use of the black-and-white somberness that dominates the film as a base for the effect achieved when the film bursts into color. This had already been used effectively, especially in "The Portrait of Jennie" with Jennifer Jones and Joseph Cotten, another masterpiece of cinematic artwork, but here it is more demonstrative, as if the contrasts between the dark gloom of hell and the paradise of the secret garden needed accentuating. It was remade in 1994 by Agnieszka Holland all in color, which definitely transcends this earlier version, abstaining from the horror ingredients and sticking more convincingly to the story with emphasis on making the psychology work. Nevertheless, both versions are well worth seeing and returning to, in some ways complementing each other, this one as the more dramatic and Holland's as the more beautiful. Of course, on such a great and enchantingly constructive story about lovable children bringing life into a world of decay around them, no film could fail.

... View MoreA Time when the Innocence of Childhood was Enhanced with a Dreamlike Quality that was Both Inspiring and a Bit Scary. This is a Classic Tale, Mostly Written for Kids (especially Girls), that has been Filmed a Number of Times. It Seems the Best Version is this One, Perhaps because it was made when these Children were Still able to be Children.The Move is a Wonderful Gothic, Fantasy, Semi-Horror Movie that is Thick on Atmosphere and Emoting. The Tantrum Scenes may be Dated and Somewhat Hard to Take but They are Short and the Film Moves Away to Other Things that are Poignant and Impressive.All Three Child Actors are Superb and the Adult Cast is Nothing Less. This is a Film that is Strikingly Saturated with Warmth along side a Foreboding Landscape of Suppression and Psychological Maladies. it is Quite Different in the way it Blends Hopelessness, Alienation, and Buried Desires Resurrected by the Sheer Will of the Innocents and Manifested with Spiritual Healing.A Near Perfect Movie that is a Throwback to a Different Era to be sure but Beneath the Layers of Dated Class Structure are Timeless Lessons that are Designed to Teach Children but it is the Children who End Up doing the Teaching.

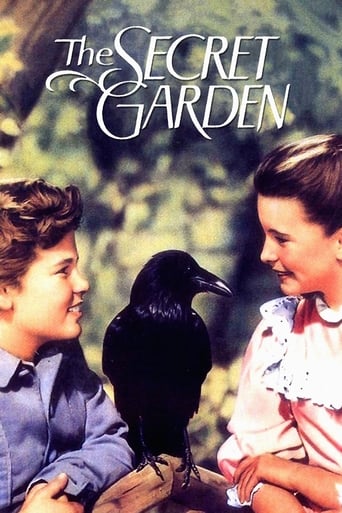

... View MoreThis is the Margaret O'Brien version of this timeless story, which is based upon the famous children's' novel by Frances Hodgson Burnett. It is not only for children, however, but also for young at heart adults. Its underlying themes are surprisingly adult, namely grief, loss, and despair, and the possibility of redemption through the power of the imagination. First filmed in 1919, this is the second cinema version of the story, which has been filmed a total of five times as a feature film and three times as a TV series. Agnieszka Holland directed a superb version in 1993, two years before TOTAL ECLIPSE (1995, see my review) and four years before WASHINGTON SQUARE (1997, see my review). But although I like to 'go Dutch' by watching Holland, her version does not surpass this one. The uncle threatened by madness through grief is here played absolutely perfectly by Herbert Marshall, whose raving despair is pathetically convincing. And in the lead we have the incomparable Margaret O'Brien, who could easily 'carry' any film she was ever in. Although the initial scenes in India are a bit stilted in this version, as soon as we get to England and the gigantic Yorkshire mansion surrounded by its 'wuthering winds', as Gladys Cooper, the terrifying housekeeper, calls them, and lashed by unremitting rain and storms, we have settled in for a traditional tale which is going to be well told. This is all aided by a magnificent performance as the country boy Dickon by the child actor Brian Roper, who retired from acting eleven years later, in 1960, and died in 1994. But this performance of his lives on in the memory. Young Dean Stockwell also does very well indeed as the crippled boy Colin Craven, though he overdoes his tantrum scenes, and that was a serious failing of the director's, in allowing all the tantrum scenes to be unconvincing. Among the stars of this film are a brilliant tame raven and a tame lamb and fox cub. I have been unable to discover the name of the raven, but he deserved a Bird Oscar, because he is in so many scenes and did such a superb job. Elsa Lanchester plays an eccentric maid named Martha who has the curious characteristic of never stopping laughing. That is not an easy role to play, but she pulls it off. Try never stopping laughing and see what I mean. This film employs the device used ten years earlier in THE WIZARD OF OZ (1939), of turning from black and white into colour at significant moments. Here, the colour occurs when they enter the Secret Garden. There is a profound psychological significance to this Secret Garden, which the grieving Herbert Marshall has kept locked for ten years so that no one dare enter it, because it represents his living heart, to which he has barred all access, as he has attempted to seal himself off from feeling after the death of his wife. Naturally, it is the spontaneous innocence of the children which achieves the access to this locked and forbidden area, both of the grounds and of the psyche, and achieves a renaissance of joy in a withered remnant of what had once before been joyful. That is why I call this story timeless, because it has all the elements of a successful myth, told simply but full of meaning. And that is why it has resonated so deeply with the public for more than a century. However, as innocence is no longer fashionable or even respectable, and as all children are meant to be forced to have sex education at the age of five, eight year-olds are on crack cocaine, and ten year-old girls are getting pregnant, all without even a blush to the public, and all wholly taken for granted, I suppose that the days when THE SECRET GARDEN could speak to anyone are soon due to expire. This is called, in case you had not noticed, the terminal decadence of civilisation. Sometimes our powerlessness to do anything to stop this accelerating decline of the world in which we live leads one to watch a lot of old movies, just in order to recapture the time before things got so bad. Even the worst days of the world wars, and the most sinister of the old films noir, were not as menacing of the blunt and inescapable reality of today's world, as it hurtles towards its inevitable doom, because it has lost its heart, or should I say, its Secret Garden. There is one more thing I should say about this film, which is a remarkable irony, namely the fact that its screenplay is by Robert Ardrey (1908-1980). Younger people of today may never have heard of Ardrey, but in 1961 he published an international best-selling book, African GENESIS, which had an incredible impact upon modern culture and transformed the public's view of humanity's origins. It was followed by another book, THE TERRITORIAL IMPERATIVE, in 1966, and others after that. Ardrey was an anthropologist, and he propounded the 'killer ape theory' of mankind's origins, whereby deep-seated violent aggression was built into our makeup and at the basis of much or most of human behaviour. The entire 1960s saw a ferment of feverish discussion and debate about Ardrey's views, and they were discussed continuously in the press and in other people's books for years on end, well into the 1970s. Much of what Ardrey propounded in 1961, which shocked the world, is now accepted without question by society in general. How strange that the screenplay to this film THE SECRET GARDEN was written by the later author of African GENESIS! There would seem to be no two works so far apart as those. Ardrey was one of two 1940s Hollywood screenwriters who would later have a mammoth intellectual impact upon Western society, the other being Ayn Rand, who scripted LOVE LETTERS (1945) and her own brilliant THE FOUNTAINHEAD (1949).

... View MoreI have watched both versions of this film, the original which is this 11949 movie, and the re- make of 1994. The kids - who are all the lead characters - are annoying in BOTH films! They are so irritating I wouldn't watch either version again.Here, young Margaret O'Brien fakes an English accent which immediately makes her annoying to hear because her accent is obvious. Her character, "Mary Lennox" pouts, most of the time and I don't find that entertaining. Her constant simpering also is revolting. This is better than the re-make, however, which also throws in New Age baloney, typical of something done in the '90s.At least in this classic film, we get to see people like Herbert Marshall, Dean Stockwell, Gladys Cooper, Elsa Lanchester and Reginald Owen, all well-known and established actors. In the re-make, the only actor of note is Maggie Smith.This is a young girl's movie, and little else. If you are adult male, don't watch either version.

... View More