Malle's landmark 1958 film is a fascinating study in selfishness. Bravely taking two thoroughly unlikeable characters as its leads, it examines their motivations and passions as they conduct an extra-marital affair.Throughout, use of voice-over and close-ups to reflect emotion emphasise that this film is largely a character study. Moreau's character, Jeanne Tournier, is established from the outset as superficial and materialistic, seeking desperately to keep apace with her more successful friend who married a Parisian.The languid pace of the film mirrors her bored, listless existence.Her lack of gratitude when help arrives when her car breaks down points to how self-centred her whole existence has become. Seeking to mirror her friend's wealth and power, she treats her helper, the young academic Bernard, as though he were a paid chauffeur, ordering him to do her will. His lack of wealth is apparent from the fact that he drives a Citroen 2CV. Only when he defies her and outright rejects the vanity of her friends is a deeper interest in him aroused.Malle, however, subverts any notion that Bernard will provide a moral centre to the film as it is he who joins Tournier on her next affair. Hence both the wealthy and academia stand accused together of moral bankruptcy.The final scene echoes the ending of Ibsen's play the Dollhouse (just as controversial in its day) when Jeanne Tournier chooses to abandon her child to find happiness in her new life. However, there is no indication here that the relationship between Tournier and Bernard will last: he seems to be just another of her passing fancies and one of whom she is likely to soon grow bored. Furthermore, there is no proto-feminist statement here as in the Dollhouse - Jeanne is merely acting to satisfy her own desires, not to make a moral stance for independence. She receives no comeuppance at the end and no heavy-handed moral lesson is given.Just as in real life, she will not face immediate consequences for what she has done but there is a sense that all will not end well for her when this affair collapses. With no social standing of her own, she will be reliant on her friends' whims of generosity and they may grow bored with her. Indeed, her social standing may eventually fall. She is seemingly floating through society with her lover just as she floated on the boat, without direction or purpose.The child is a marginalised figure in the film and has no real voice of its own yet its prominence in the final act emphasises what Jeanne is sacrificing, with seemingly very little concern. Likewise, her husband has no real voice but this reflects his emotional distance from her. The audience do not really come to understand him, just as Jeanne does not, though on her part it is due equally to her lack of effort.Ultimately, this film then gives much insight into why extra-marital affairs occur. However, due to Jeanne Tournier's vain and superficial nature, it is hard for her character to sustain one's interest for the full running time. Just as she becomes bored with those around her. we become bored with her.The languid pace ultimately becomes tiresome and the climactic, erotic scenes seem very demure by today's standards, leaving one with an unsatisfied feeling at this dated film.In making a story about superficial people, there is always a risk that the film itself will end up being superficial and, while Malle does his best to avoid this trap, one can't help but feel he wasn't entirely successful.

... View MoreA married woman (some years after concluding a successful affair, I might add) once lectured me that love was about commitment and being able to get on with one another. Perhaps, I thought. Except poetry and perhaps French literature especially, gives the word a somewhat more vibrant texture. A meaning many of us will still maybe yearn for and powerfully - in our heart of hearts.'Jeanne' in this film is played by Jeanne Moreau. Beautiful and sexy. She is trapped in a marriage of monotony. Husband is a successful newspaper publisher. Their Dijon country château is one of understated wealth. Industriously posh establishment, if you like.Jeanne visits her friend Maggy in Paris regularly. Maggie is trendy and superficial. She approves of Jeanne's affair with Raoul, a rather buff polo star. Unlike Jeanne's husband Henri (who, it must be said, is a boring old fart), Raoul is attentive and adoring. Society chic, if you like.Into the mix suddenly appears Bernard, an archaeologist. He hates Maggy's in-crowd describing them as 'flavour of the day.' He is probably everything Henri would be if Henri had a life. (Henri has years of slaving in a publishing house. Plenty of money. Plenty of nice furniture. Including a wife.) \He politely welcomes Bernard, who has rescued Jeanne when her car breaks down.If this were a rom-com you'd guess the rest. Queue steamy sex with artistic lighting. And while Les Amants gives you plenty of what you expect, it also gives you plenty of what you don't. Unresolved moral quandaries if you like, or not.It was the moral outrage a married woman leaving her husband and children after a night of sex that probably led to obscenity charges on its release in America in the late fifties. Far more than the momentary nudity. The latter seems mild today. Yet the film is as fresh as it was then. As challenging as it was then. And as beautiful.Les Amants is shot in immaculate black and white. The men playing polo. The exquisitely photographed French countryside. And a Brahms (Sextet in B-flat Major) leitmotif which both immortalises the passion and encourages us to attach importance to its emotional and aesthetic qualities. Jeanne's first world (with Henri) is dead and empty. Her second (with Raoul) is a pleasant distraction but shallow. Visually and verbally, Bernard connects to Jeanne in an altogether different way. He makes her work for it but then rewards her. Henri makes her work for attention but doesn't give it. Raoul showers it on her with no effort on her part.Bernard ignores Jeanne's 'damsel in distress' pitch when her car breaks down. "Engines and I don't see eye to eye," he tells her. Until Jeanne breaks out of her pathetic helpless-female stereotype he is uninterested. He makes her to laugh, comparing her husband to a bear. We see Jeanne making a determined effort with her appearance. Bernard's poetry wears her down. He fills her head with visions of how beautiful the night is and then associates her vision with how he sees her. He awakes the divine in Jeanne "Her angel's smile gleamed." The moonlight tryst sees light rippling through leaves onto water. Bernard frees the fish caught by Jeanne's husband's traps. He is freeing her spirit from her dark depths. His intrusion (like the bat and flies at the house) is first seen as a threat. But it is her freedom he acknowledges, that she has denied herself, that is too horrible to countenance. "Is this a land you invented for me to lose myself in?" she asks.Jeanne realises that the part of her she dreads the most is the only thing that makes her feel alive. "Her world is falling apart. A hateful husband and an almost ridiculous lover. The tragedy Jeanne thought she was in had become a farce. Suddenly she wishes she could become someone else." Readers may recall the not too dissimilar dilemma of Julianne Moore's character in The Hours. She leaves a husband and child and disappears to become someone else. In that story, no lover complicates the dilemma. She is simply suffocating. We are tempted to condemn Jeanne's action because of her night of passion. But she is similarly escaping from an impossible life. A duty to her husband, yes. To her offspring, of course. But isn't the highest duty to her own being, her own life? And it is not as if Bernard is a philanderer. He wants her for always. But instead of reassuring us that everything will turn out well, director Louis Malle realistically allows our protagonists to acknowledge that they face an unknown. They are well-suited there is none of the narrative primitivism of, say, Women in Love. But Les Amants is a film of emotional and moral honesty. No wonder it shocked the bourgeoisie. And American values.The obscenity charges in the USA went to the high court. Justice Potter Stewart overturned them and made his famous pronouncement on pornography: "I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that." European films of this ilk helped to push the bland American film-making of the time towards greater artistic freedom. Les Amants established Jeanne Moreau's on screen image as a sexually independent woman. Her strong performance as someone responding to three very different life choices cemented her onward career.This is a film of courage, of a sophisticated beauty singing in tune with her own nature, rejecting the limiting values of industry and society. It is the story of a woman finding she is the equal of man and finding a man that is her equal. The last portion is perhaps overly sentimental. But it is sentimental about the dark night of her soul. Not a disneyfied happy ending. If you are shocked after seeing the film, ask yourself why.

... View MoreLouis Malle's Les Amants is the most romantic film ever made. Screw subjectivity and critical judgment. I've just come off fresh from seeing it, and, in the spirit of the film, I'll let my excitement wash over me instead of letting it die down to see it coolly. Seeing it gave me one of those precious moments, moments where you gasp and go oh-my-god, disbelieving your eyes that cinema could go to places like this, and make you feel things you never felt were possible in fiction.Buried within the Optimum Releasing of the Louis Malle box set, but it emerges the most deafeningly romantic, even when compared to the already celestial ending of the more famous Elevator to the Gallows. Its blissed out view on happiness makes it impossible to attach any critical adjectives to it; it requires us to suspend all thinking faculties and just go with that one powerful emotion.It's amazing how it turns what could've looked like a cover of a chick romance novel into something this beautiful. Henri Decae, who almost single-handedly created the first images of the New Wave, literally sets the screen aglow in ecstasy, painting the two lovers in a heavenly light in that pivotal centerpiece, which is one of the greatest moments of cinema, bar none. Even Jean Vigo's L'Atalante holds nothing on this. (There will be spoilers from hereon, and I would urge you to stop reading this paragraph if you've not seen the film. The joy of discovery in this film is so much more than any other film I've experienced, that I'm wholly convinced that one should experience this as fresh as a virgin.) Stripped of their daily pretenses and graces, the two lovers traverse a God-made Eden, becoming simply Man and Woman and reuniting again, several millenia after the First Man and First Woman were expulsed from paradise. When Jeanne Moreau takes Jean-Marc Bory's hand and asks him 'Is this the land you created for me to lose myself in?', the gaze is sealed and the viewer can do nothing but share in their passion. The two lovers become such eminent symbols of love, sex, and happiness that it's hard to imagine anything more sensual and erotic than this, especially when compared to the fully colored and fully exposed sex symbols of today. They belong to an era removed from any other, not the era that the film was made in, but a black-and-white, pristine era that exists only in cinema, one in which true love still exists without the moorings of reality.And the decided lack of moorings in this film is what makes it so bewitching. Whether it's the fleeting white horse or the eyes of the beautiful beautiful Jeanne Moreau, the film doesn't look back, but indulges fully in the moment, that moment of sensuousness. It is so fitting that the film should be called Les Amants, because anything else would be pretension - the lovers become the lovers of any era, any millennium, by their love alone they have been elevated to the great lovers that have long passed. They transcend being, nature, rules and become one - spirits entwined - with a world that is beyond the tangible, such that any rational reasoning will not be understanding. It's a magical world, a fantasy world, a world that is as unreal as we want it to be real. And this world, the film proposes, can only be reached through a temporary moment of love, un-selfish, immaterial, illogical, and unquestioning love. And when you're able to give yourself in, together with the film, it suddenly becomes so clear and not that unreal anymore.At the risk of sounding like a nut, I just wanted to recommend this film to everyone who thought that this century has made us cynical. Cinema, which began and evolved with this century, has rarely stepped out of its time so gloriously that it becomes a monument, a structure of those classical (and probably impossible) days. It is the single most ravishingly beautiful moment in the history of cinema.

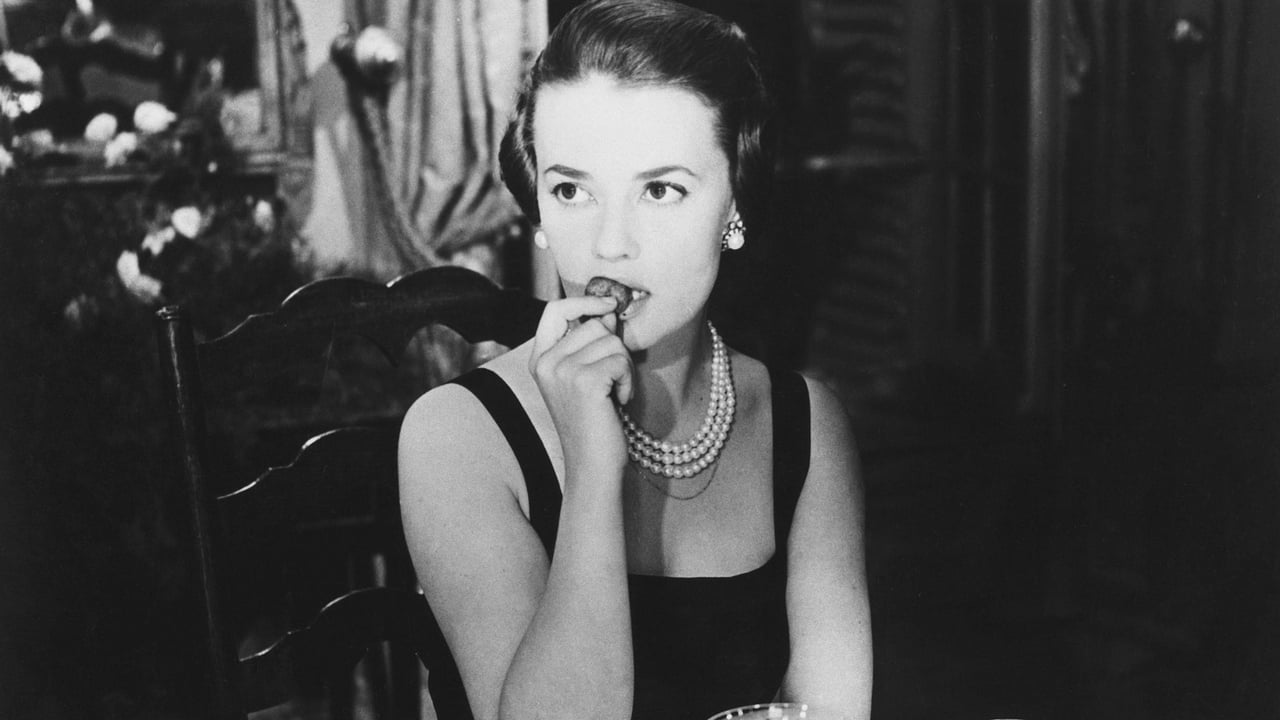

... View MoreWhat you see here is Jeanne Moreau's famous first filmic female orgasm and director Louis Malle's second feature film. Les amants / The Lovers was at that time a controversial study of bourgeois emptiness and sexual yearnings. The (as widely described) inscrutable Moreau plays a high society wife who is bored by her rich husband, has a lover, smart friends and a daughter. On one night she makes passionate love with a young student of a few hours acquaintance, and leaves it all for a new life.If it now looks too much like an angry young sensualist's movie, the combination of a body language that is highly pleasurable, the soundtrack of Brahms, and the Henri Decaë's velvety monochrome, ravishing photography proves hard to resist. Her second collaboration with director Malle shows once more, what a wonderful screen persona Moreau is: commanding, willful, sultry.

... View More