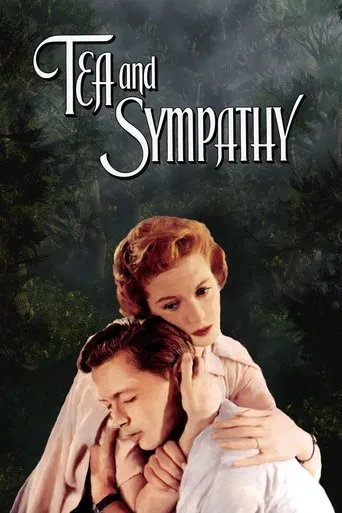

Vincente Minnelli's "message" movie TEA AND SYMPATHY is excellently crafted with Golden Hollywood poise, rehashed for the celluloid by Robert Anderson from his own stage play, it reunites the original play's three leads, Deborah Kerr, John Kerr (no, they're not related) and Lief Erickson. In spite of its antediluvian views on masculinity, the film appositely re-surfaces as a searing melodrama zinging at today's intolerant world, where egregious persecution is wantonly inflicted on minorities and non-conformists.Tommy Lee (John Kerr) is a 17-year-old prep school student, he is ostracised by his jock classmates who coin him a sobriquet "sister boy", why? Because of his curly hair, his gait, his sewing skill, his inclination of classical music over sport and roughhouse (he excels in tennis though), he reads Voltaire's CANDIDE and the fact that he has never bragged about girls. All these facile symptoms can be nimbly dismissed as specious by a more rational mind (even in its time), like Tommy's roommate Al (Hickman), who always stands up for him but the real helping hand comes from Laura Reynolds (Deborah Kerr), wife of Tommy's macho coach Bill (Erickson), who is transparently not in line with his wife's sympathy over Tom. The title refers to the common "interested bystander" stance which Laura is advised to take being a woman in her position - "doesn't go beyond giving him tea and sympathy on Sunday afternoons".Bearing mockeries and mobbing from his peers, contempt and grudge from coach Bill and mounting pressures from his father Herb (Andrews), Tommy starts to unravel in spite of Laura's intransigent support and growing affection, in a last-resort attempt to prove his manhood, he arranges a rendezvous with the local loose girl Ellie (Crane, a chain-smoking waitress depicted with a broad and vulgar stroke), Laura overhears it and in her last-resort attempt to pre-empt a disastrous wind-up, she puts on her fancy blue dress and manoeuvres a tête-à-tête to procrastinate Tommy's action, during which she discloses the death of her late first husband, who died young just because he was trying to prove something that he needn't proving, so as to convince Tommy that he shouldn't follow the same old road to ruin. Here, Laura's motivation has been cogently vindicated, she has been a victim of the bigotry and prejudice of the rank masculine and patriarch society, so how can she just sits and doles out her tea and sympathy?Nevertheless, Laura doesn't stop the disaster since she backs off from Tommy's desperate advances which later she regrets, also because obviously, the story needs something more dramatic to grab the attention and up the ante, yet, the movie is cleverly introduced through the lyrical recollections of Tommy a decade later in a classmate reunion, so Minelli assures audience in the very beginning that Tommy comes safe and sound out of his trials and tribulations unjustly cast upon him. In the beautifully arranged woodland scene, as if in a dreamlike fairy land, Laura comforts a distraught Tommy who has survived a suicidal attempt, with her kiss, the purest and tenderest kiss from a woman to a sensitive young man on the cusp of adulthood and whose nature is in the danger of being cruelly oppressed, even not being typecast as a nun, Ms. Kerr's Laura continues carrying out the name star's holy mission to save lives. There is gratitude in that kiss too, through Tommy's predicament, Laura finally can face up the marital hurdles between her and Bill under the surface of superficial harmony and make a right decision for her own sake.John Kerr is another young talent whose acting career failed to launch after a promising start, he fleshes out Tommy's vulnerability, sensitivity and perplexity, but righteously opts not to emphasise on queer mannerism, in fact, he is fairly attractive as an object of desirable for girls (and boys too, of course), the trenchant irony is just self-evident when Al tries to correct Tommy's unorthodox walk, those accusations are so inadequate and ridiculous. Fault-finding can flourish on everything and anything, which soundly advices us to nurture a discerning eye in lieu of hastily jumping on the bandwagon. Character players Leif Erickson and Edward Andrews, the former lands a meaty supporting role as the narrow-minded coach, in every step, he manages to show beyond doubt that Bill is unworthy of Laura's merits, and possibly, he is a deep-closeted homosexual himself, Erickson's butch appearance holds sway in a ghastly dislikeable role; as for the latter, in his more nuanced brew of pleasantry and angst, Andrews comes out as a more assured propeller to push Tommy into the abyss.In retrospect, 1956 should have been Ms. Kerr's Oscar-reaping year, only if she were nominated for this film instead of the hyped pap THE KING AND I (1956), as much as I worship Ms. Ingrid Bergman, her Oscar-winning performance in ANASTASIA (1956) is no rival compared with Ms. Kerr's consummate cri-de-coeur against the omnipresent scourge lurking underneath every imperfect soul. Ms. Kerr is such a pioneering "queer" icon to be reckoned with, especially in view of a less liberal era, whose legacy and glamour need to rediscovered by younger LGBTQ generations, forever dignified, you can never sense a tint of condescension in her refined presence, and her Laura Reynolds, what a courageous woman and what a tour-de-force to witness!

... View MoreI have to admire "Tea and Sympathy" because it tackles so many interesting and important issues. Now I am not saying it necessarily does this well in every case, but it sure is a film that can stimulate some conversations between folks who watch the movie.The film begins with a rather awkward young man, Tom (John Kerr) talking with the wife of one of his teachers. Laura Reynolds (Deborah Kerr) is very understanding and likes the guy and spends a lot of time with him. As I watched, this sure set off an alarm within me--this is a VERY dangerous situation. The film's focus is on Tom's being effeminate and sensitive--a 1950s way of saying he was gay. Most of the guys in school dislike and taunt him--and his own father is ashamed that the boy doesn't attain some masculine ideal. Yet, despite this, Mrs. Reynolds cares deeply about the boy--too deeply.Where all this goes is very predictable in many way, but I also feel that the film actually narrowly missed hitting a bullseye. It focused almost exclusively on the young man and never really alluded to why this older woman would eventually be sexually intimate with him. It seemed to say it was an act of love and she did it to help the boy in some convoluted way. However, HER needs were an important part of all this. She was trapped in a loveless marriage with a man who was overcompensating so much that it seemed as if he was gay and certainly not the young man. To me, this is a very important part of the equation and wasn't adequately addressed in the film. Now I am NOT saying it's a bad film--I am just saying that the film seemed to put too much emphasis on the young man when I actually found the wife and her motives much more interesting.Despite this MINOR complaint, I loved that the film dared to focus on what it is to be a man. Sensitivity, not fitting in and how kids scapegoat and mistreat these loners is a wonderful topic that should be talked about much more than it is. I remember lots of nice guys who were horribly mistreated, beaten up and labeled gay as I grew up--simply because they were different. This is something every father SHOULD talk to their boys about--and watching the film with your teens is a pretty good idea.In addition to this minor complaint I have one more. In the original play, the story ended with the sex act. I don't like this because it seemed a bit irresponsible plus it placed too much emphasis on the sex act and not the motivations. I also didn't like the ending MGM slapped on it because it came off as too preachy and long-winded. Again, however, the good stuff greatly outweighed this.Oh, and why is it that practically every film about high school kids in the 50s starred 'kids' who were in their mid-20s or older?

... View MoreThis powerful drama is based upon a hit Broadway play by Robert Anderson, which ran for 712 performances between 1953-1955, directed for the stage by Elia Kazan. The three leads in the play are the same ones who star in this film, namely Deborah Kerr as the wife of the house master at a boy's boarding school in New England, Leif Erickson as her husband, and John Kerr (no relation) as the 18 year-old boy. Vincente Minelli, who directed this film, therefore inherited a cast who had 'been in rehearsal' for two years for their parts! They could not be more brilliant and effective, and this is one of Deborah Kerr's performances to rank with her appearance in FROM HERE TO ETERNITY (1953), which immediately preceded the three years she was to devote to this role, both on stage and on film. This film also launched the young John Kerr (who died this month aged 81) into such prominence that he got his lead role as the Lieutenant (or, as Bloody Mary calls him, 'Lootellum') in the film SOUTH PACIFIC (1958), where he became a 'national treasure' as 'that nice young boy who is so charming', and became beloved by the very Middle America which had been so shocked by this film only two years earlier. Although the social mores and context of this story are inevitably dated, this is a very intense and profound drama, with a great deal of effective satire in it as well. Although this story was successful in the sophisticated ambiance of New York City, when the film was released, there was shock and dismay throughout Middle America. After all, this was the first time a major Hollywood film had ever seriously dealt with the subject of a romantic relationship between a schoolboy (albeit that he was safely described as being 18, and hence was no child) and the wife of a schoolmaster. This was considered so shocking outside of the metropolitan communities of the two coasts that the film was massively controversial, and many were the matrons who condemned it for immorality and for destroying the moral fabric of the nation. The film treats this subject with the greatest possible sensitivity, and there are no scenes of anything more explicit than gentle kissing. One is left to imagine the things which are now shown in closeup in every movie as a matter of course, namely what I call 'the rutting scenes'. (Why is it that nowadays everything must be explicit, and subtlety is a forgotten art? In films now, it is not sufficient for people to copulate, they must be seen to copulate. Prurience has been elevated to the pseudo-status of a cinematic virtue and a commercial requirement. Just as many actresses who refuse botox cannot get parts, actresses who refuse to take their clothes off and grunt and groan in closeup also cannot get parts. And if they refuse to 'show their tits', then they might as well resign from SAG and retire. This is, of course, an example of extreme social decadence and a sign that Hollywood cinema has lost its capacity for imagination.) In this film, Deborah Kerr manages an American accent as well as usual, though her tremulous voice throbbing with emotion is unchanged from her English roles, and is marvellously moving and effective. She grew up in the obscure town of Weston-super-Mare in Somerset (which also gave birth much later to that bizarre person, John Cleese), and that is a strange place mingling the surreal with the stupefyingly mundane, a true place to flee from, and which is sufficient to make any girl's voice tremble with suppressed expectations and a fluttering of anticipated flight. This Weston background of Deborah Kerr is little known, and I discovered it by watching many years ago a documentary film about her youth made for and shown on the regional West of England ITV station, which I believe was never shown nationally. Some people who knew her as a girl were interviewed. I believe I have it on tape somewhere. It seems that Deborah Kerr was never eager to call attention to her years in Weston, and preferred to mention having attended school in nearby Bristol, which is a small city about 20 minutes from Weston by car. This film is full of savage satire about the athletic boys who sometimes dominate boarding schools and some universities, who are known as 'jocks' (named after their jock straps which they wear when bashing each other's heads in, not to mention their crotches, at football and anything else which is violent). Such testosterone-fuelled lunatics can be extremely abusive and threatening to more sensitive boys, as we see in this film, and as must have happened to the author, Robert Anderson, to judge from his intense feelings on the subject. I was fortunate that at my boarding school, though everyone was mad about sports, 'jocks on the rampage' did not predominate, but I have visited other campuses where they did. And I can tell you there is nothing so revolting as the smell of sweaty jocks' socks at a boys' boarding school. So you have been warned! The dormitories reek of the sour, foetid odour so that one is nearly sick. You can smell it in the film, and it is enough to make the delicate Deborah Kerr even more tremulous, not to mention John Kerr who longs to flee from the nightmare of his school, but whose father is a former 'jock' who wants 'to make a man of' his son. And that leads me to this question: why is it that a boy is supposed to be a jock before he can become a man? This film attacks the world of jocks with unremitting hatred, and those of us who hate their sweaty socks can all sympathise. But I do not see this as 'a gay film'.

... View MoreTime has been less than kind to this movie which must appear as something of a cross between satire and parody to an audience today. In 1953 on Broadway Robert Anderson's play - featuring the three principals from the film, Deborah Kerr, John Kerr and Leif Ericson - was a sensitive treatment of a still sensitive subject and even in 1956 Anderson was forced to sanitize his screen adaptation; in the play Tom albeit naively has been swimming in the nude with a Music teacher who subsequently lost his job, a much sounder - though still slightly suspect - basis for marking him queer, and his nickname was 'Grace', based on nothing more sinister than his favourable comments about a Grace Moore movie. Here, Anderson substitutes the slightly bizarre 'Sister Boy' for Grace. Perhaps the worst sin of all is the framing device whereby Tom attends a Class Reunion as a grown man and then thinks back to his time as a tormented schoolboy, but worse is to come; in the play Anderson came up with one of the all-time Great curtain lines: In a mixture of compassion, admiration and a need to make Tom realise that he is NOT gay she offers herself to him with the lines 'years from now, when you talk about this ... and you will, be kind'. Minnelli includes both scene and line - albeit switching the location from indoors to outdoors - but then instead of FADE OUT he returns to the present with Tom calling in to see Kerr's house-master husband who gives him a letter that Laura has mailed from wherever she is. The letter serves to tell us that Tom is now married (so he CAN'T be gay, right) and has written a book about his time at the school and his relationship with Laura. Totally unnecessary and making what once must have been a half-decent film even more risible.

... View More