Firefighting films was probably one of the most popular early film genres of the silent era. This is understandable; audiences were normally treated, when this film was made, to short snippets of everyday life: babies being fed, dancers performing, etc. This film is far, far from being the first of these firefighting films (years before, in 1896, Edison made many different films that were static shots of firemen racing to the rescue, and several fire rescue scenes) but this is one of the very first films to actually make a story out of it. Unlike Edison's previous static scenes of fire rescues, this film has multiple shots; nine in all, and manages to tell an exciting story at the same time that can be easily followed.While Edwin S. Porter made some ground-breaking steps in the making of this film, it cannot be denied that the film is a remake actually of James Williamson's "Fire!" drama from 1901. Two years earlier, that film was much simpler: instead of nine shots there are four; the film is shorter with a running time of five minutes instead of seven; the pace itself is faster. Porter's remake is much more elaborate and expanded on Williamson's ideas. The film begins with a postman (I think it's a postman) dreaming about the fire starting through the use of a matte shot. He sounds the alarm, and the firemen come and save the mother and child. It's a pretty simple story but the way it's told is more important. Yes, it is sometimes a drag; I find watching it with music makes it much more enjoyable. While there isn't much to it, it was one of the most well-known movies of its era, and thus is a must-see for silent film buffs.

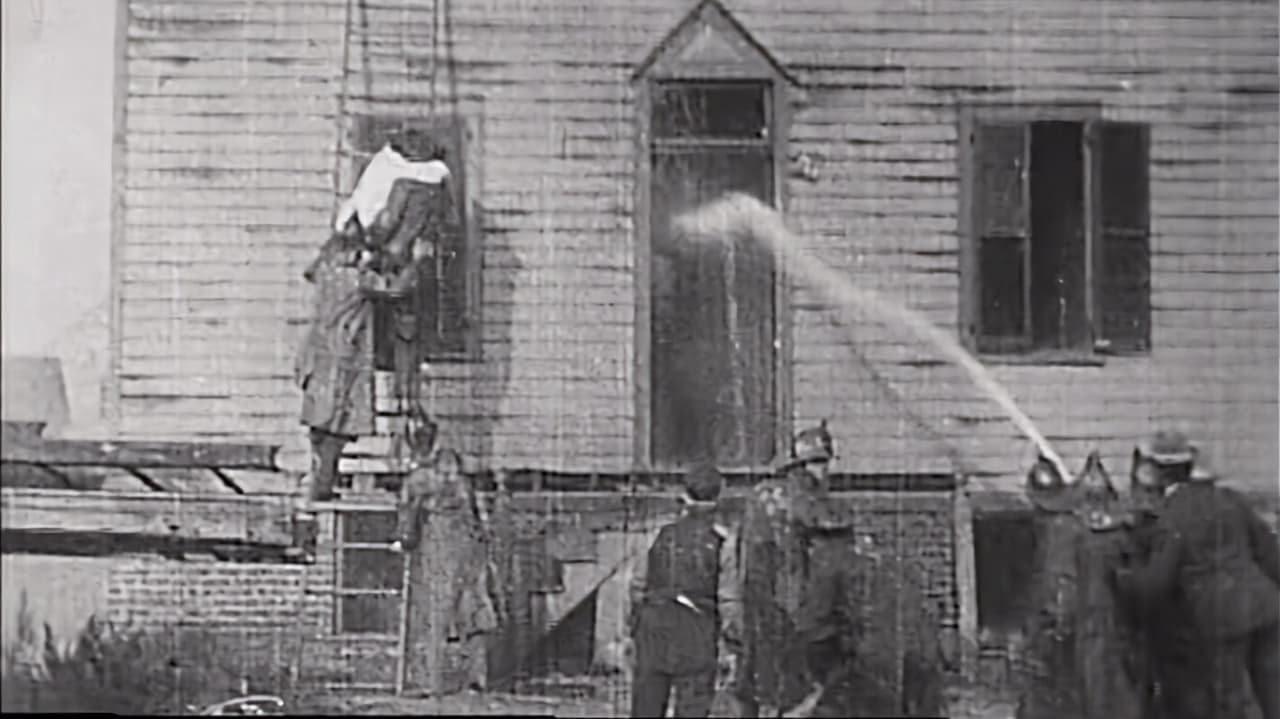

... View MoreThis film, with nine shots lasting around six minutes, is often seen as a dry run for director Edwin S Porter's major breakthrough with The Great Train Robbery, released later the same year. Both use themes with plenty of opportunity for action and movement, and indulging audiences' taste for experiencing danger vicariously. But Life of an American Fireman is more interesting for the storytelling ideas that didn't make it into the later film or, indeed, into the developing language of mainstream narrative cinema.The film opens rather oddly on an optical effects shot of a dozing fireman, with his daydreams of a happy woman and child, presumably his own family, in a fuzzy circular mask to his right, a device borrowed from graphic art. This reverie is rudely interrupted by a striking closeup of a street fire alarm. The firemen then spring into action, speeding through the streets of a wintry New York City and its suburbs. They rescue a woman and child from a house fire, creating a thematic link back to the beginning and reinforcing the image of the fireman as heroic protector of families and communities, as befits his emerging role as a public servant – an integrated, professional fire service for the city had only existed since 1898.The depiction of the rescue exhibits the oddest structure to modern eyes (although there's something of the same thing going on when the fire engine leaves the station). First we see a woman in a smoke filled bedroom crying for help at the window and then collapsing on the bed. A fireman bursts through the door, lifts the woman and carries her through the window down a now-waiting ladder. Seconds later he returns through the window, lifts a previously unseen child from the bed and disappears through the window again. Porter then shows us the same sequence of events again from outside the house: the fireman enters the house, the woman appears at the window, the fireman descends carrying her. Watch the bottom of the frame as they reach safety (yes, it's another of those crowded long shots): the woman recovers and begins gesticulating distraughtly. That's why the fireman returns up the ladder for the child.The conventions of continuity editing shortly to be defined by D W Griffith and others dictate that consecutive events with a causal link take place in a single continuous time frame when depicted from different angles or even in a different location. This governs the principles of cross cutting, which would certainly be the default if a modern film maker were to shoot this story, cutting away to an exterior shot to show the recovering victim motivating her rescuer to return to the burning room, and then back to the interior again to show him lifting the child. In fact continuity editing is just as artificial and conventional an approach to narrative as the one demonstrated here. Continuity editing creates the illusion of continuous time by cutting together shots that were invariably filmed at different times, and sometimes in completely different places. Yet it is now so fluent and familiar it seems natural, and so hegemonic that films that deliberately break its rules are seen as marked, experimental or trying to make a specific point: for example Rashômon and films inspired by it, which repeat the same events from different perspectives with subtle differences in order to challenge the audience's acceptance of the truth of what is shown on screen.So intolerably odd did Life of an American Fireman seem to a later distributor that it was reedited to inter-cut the shots, which led to it's being hailed, rather ironically, as an early example of cross cutting. An examination of a paper print version in the 1990s revealed Porter's original montage.Porter's film was very likely inspired by an earlier film from Britain's Brighton school, Fire! (1901), shot in Hove by James Williamson. This depicts an essentially similar sequence of events in only six shots, and though Williamson is less adept at handling the action than Porter, with much faffing around harnessing the horses and less exciting depictions of the fire engines racing through the streets, the burning bedroom (near-identically laid out to Porter's though with a male rather than a female victim) looks much more perilous, with real flames. There's no repeated continuity during the rescue sequence but instead an excellent early example of a 'match on action', with the cut between the interior and the exterior made precisely at the moment when the fireman first emerges through the window, logically linking the two shots. Williamson stays with the exterior to show the fireman returning for the child.

... View More. . . as opposed to the grand documentary suggested by the Edison title. I've seen many bits and pieces from this 6 minute, 45.28 second crazy quilt in other Edison shorts from the previous decade (some from possibly ACTUAL fire runs with REAL firemen!). The long ending sequence at the prop house with smoke machines and histrionic actors was especially familiar to Edison peep show viewers who were repeat dupes--I mean, customers. If you watch this mish-mash closely, it makes little sense. The part I find most ludicrous is the lingering shot of the alarm being sounded by someone pulling the lever inside a fire box. This alarm box is located on a city sidewalk, and the fire turns out to be in the suburbs at a frame house five or ten miles away! Presumably, old Tom's entertainment empire henchmen thought so little of their viewers' intelligence that they would assume a passerby could see a fire, saunter for an hour or two till reaching the big city call box, pull the alarm, wait for three different convoys of fire vehicles to reach the country, arriving just as the lady of the house (who has apparently been stumbling around in the smoke FOR 3 HOURS!) finally collapses onto a conveniently placed bed. I've heard of the suspension of disbelief, but Thomas Edison figured his suspenders reached to the moon!

... View MoreKenneth MacGowan in his book "Behind The Screen" discusses this film at length. He was familiar both with the controversial print and the paper print in the Library of Congress.He didn't think that the evidence of the paper print was conclusive.At the time, a movie could be copyrighted only as a collection of still photos, which is why the paper prints were made.For that purpose, it didn't matter whether they were in the final edited form,or even if there was more footage than in the released version.MacGowan thought that a hastily assembled negative was used to make the paper print,with all of the footage shot from one angle together.Porter therefore had more time for final editing without delaying the copyright process.The question is, if the existing copy was reedited, who did it and why? Certainly not during the silent era? by the time such editing became more common, this picture was an obsolete relict of a primitive era.And if reedited then, where are the title cards? They weren't in use in 1903 when the picture was made,but came into general use a few years later. So why "modernize" the movie in one way, but not another? It seems strange that they were not added.MacGowan admits that there is certainly a question about the complex editing, but points out that Porter took exactly the shots he needed for it.And as to why he never used it again, there are two factors. It may have been too advanced and confusing for the audiences of 1903,just as later audiences found the more complex editing of Griffith's "Intolerance" even more confusing.And there is evidence that Edison disapproved of Porter's editing.Edison involved himself in every aspect of his companies' operation, insisting on personally approving each piece of music that went on his records,for example.Which didn't help sales, as he didn't have very good taste.Edison's word was law, and Porter would have bowed to it without complaint. In addition, the Edison Catalogue of that time specifically stated that after the woman was carried out of the room by the fireman, there was a dissolve to the outside of the building,the woman pleads for the fireman to rescue the child, and he returns up the ladder.The copyright version shows the fireman carrying out the mother and returning immediately to rescue the child in one continuous shot with no dissolve to the outside.Since the catalogue is so specific on this point it would certainly seem that there was inter cutting not shown in the copyright print.

... View More