I don't think this is Peter Watkins's "best" film, exactly. It lacks the discipline and precision of "Edward Munch." But this is the purest example of the potential of Watkins's practice. Few films I've ever seen have felt as alive as a collaboration between a director and a group of performers. The non-actors, denizens of a working-class neighborhood of Paris, lived together and collaborated with Watkins as a legit, studio-based commune during their re-enactment of the events of Paris, 1871. In the film's second half, the reenactment subtly starts to occasionally give way to conversations between the performers during the course of the production. The past starts to seem truly "re-enacted," as the "present" seems to become part of a work of historical story-telling. In the final scenes, the actors seem to go into a kind of trance of fury as they sing revolutionary songs while awaiting to defend the city from Versailles' soldiers. Many turn to the camera and say that they would pick up guns to fight for a new commune in the present. As a viewer, I believed them.This film also goes farther in its critique of media than Watkins' earlier films. All of Watkins's films feature a contemporary documentary camera crew interviewing historical figures in a way that is quite confrontationally unnatural. In the previous films, the (seemingly) Watkins-led camera crews were portrayed as the allies of "the people." Here, the larger canvas allows for a more nuanced critique of even "people's media." Two media outlets vie for the hegemony of the viewer: Versailles News and Commune TV. Even Commune TV, the "ragtag, independent" news outlet is presented as always veering towards the most relatively conservative seats of power. The Commune reporters consistently defend the (I think rather inappropriately maligned) "professional" Commune leadership from the masses. (As much as I admire Watkins, he is undeniably an ultra-leftist.) I wonder, however, if this more complex take on the media is not tied to the more complex layerings of "realities" in this work that I discussed in my first paragraph. For, unlike, in the earlier films, here the "progressive" media outlet (Commune TV) is not the "highest" reality, and therefor is not directly attached to Watkins himself. It is only part of the historical fiction that Watkins implements to show his performers embrace the political heritage of the Commune. In the scenes where the performers discuss their experiences of the production with each other, Watkins name is only ever mentioned with reverence. The filmmaker deepens his critique of media, but not of his place within it as a "radical saint."

... View MoreOther viewers' comments (thus far) encapsulate most of my feelings about this amazing film (shot on high-quality B&W video, actually). I would add that La Commune divides naturally into two parts, and would be comparatively easy viewing on different nights. The most dramatic moments, obviously, are in the second half - not just the scenes of the Communards defending Paris, but seeing more of the actors commenting on the project, which is when Watkins' strategy of having them react "as" the people they are portraying rather than simply giving them lines to read, really pays off. Personally, I'm glad I was able to see the whole thing build up to those moments.But however you decide to do it, see La Commune. It will move you and make you think about your (very real!) ability to be a political actor, to make a difference, to take control of your life, even in a terrible time like the present. To use a much overused word, it's empowering.

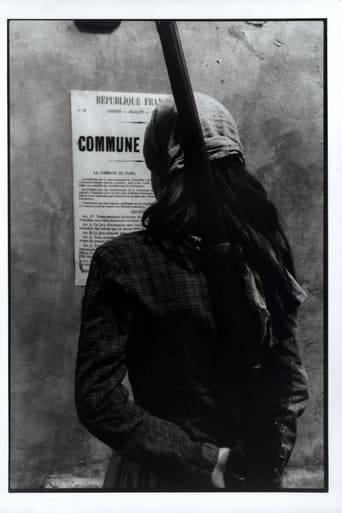

... View MoreOnce again, the National Gallery of Art film program has brought us another film we are unlikely to see at any other theater. This is an uneven but ultimately fascinating look at a relatively unknown period in French history, the 1871 Communard revolution in Paris right after the Franco-Prussian War. The filmmaker uses non-professional actors who were also allowed to be co-producers and to write their own lines to some extent. It is shot in black and white and on Beta Digital tape. The film technique reminds me of an old TV program from the 1950s' called "You Are There" in which today's media looks back on history and even interviews the participants in the historical drama.The film is very slow going which gives the viewer a total feeling of both being there right in the action on a day to day basis while looking down on it from afar. We live the everyday life of the people in Paris during this short period of 2 1/2 months. At some points, the actors stop the action and comment on their involvement in the making of the very film they are in. Also, they and the filmmaker comment on globalization and peoples' rights in today's world. History is brought forth into our present time and we see that all events in human history are more alike than they are different. This film is not for the average movie-goer. It is for a small audience of patient students of history and politics. It fascinated me but also tried that patience quite often. I would recommend not attempting to view this film without being well rested. It is in two parts of three hours each. Frankly, the filmmaker could have cut this down and still had a powerful history lesson for all of us.

... View MorePeter Watkins stands at the base of a form of historical documentaries known as 'documentary reconstruction'. Lightly based on battle re-enactments, Watkins hires amateur actors to play the roles of common people in the Paris of 1871. Famine and civil unrest cause a popular revolution, supported by followers of Karl Marx. The people take power and form a Commune, a communist government. After a few weeks, the official Versailles government regains the city by force, and tens of thousands of people are executed.Watkins' historical drama is based on the common people, which are shown in their everyday life. To do this, he introduced an anachronism: in the 1871 context, the people form a tv station. The Versaillais also have their official tv station. This way, the documentary becomes both a social project and a media experiment.

... View More