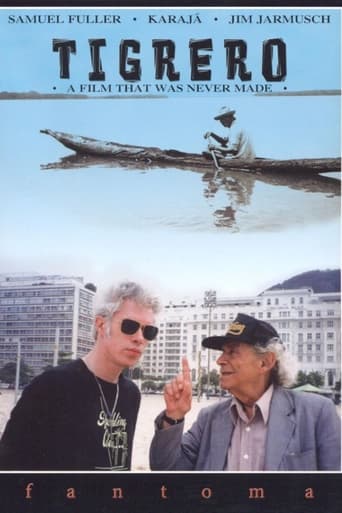

In the early 1950s, 20th Century Fox invited Samuel Fuller to make a picture in Brazil about a jaguar hunter (John Wayne was tipped for the role) falling in love with a woman (Ava Gardner) he helps to rescue as she flees through the jungle with her cowardly husband. Fuller headed for Brazil to make a preliminary study and settled in a village of the indigenous Karaja tribe. He scouted locations, shot some footage of local nature and customs, and discovered some elements that he might work into the screenplay. In the end, however, the whole project came to naught when insurance companies refused to provide coverage for a shoot in what was then a remote and potentially dangerous part of the world.In Mika Kaurismäki's 1992 documentary, TIGRERO: A Film that was Never Made, Sam Fuller returns to the same village he based himself in four decades before. American indie filmmaker Jim Jarmusch tags along as the interlocutor to which Fuller recounts the whole Hollywood story and comments on how rural Brazil has changed since his first visit. Jarmusch is also interested in the culture of the Karaja, taking photographs of the village (some of which are included as extras in the DVD release) and narrating in voice-over some of their traditions and practices. The downside of this is that the duo talk about the Karaja according to the noble savage stereotype, depicting them as an idyllic people without a care in the world, and the film never confronts the challenges they might have faced now as modernity arrives, or forty years ago when life was no bed of roses either.The film has an inauspicious beginning, where Jarmusch asks Fuller in Rio de Janeiro why he's there, and it's obvious that this whole (very stilted) dialogue is scripted. Once they subsequently reach the Karaja village, their chats seem more real. The first thing they do in the village is project the footage that Fuller he had shot forty years before to the locals. The Karaja are amazed to see their long-dead relatives and friends. As one Karaja explains the visceral impact that this film footage had on him, Fuller tells him "That's called emotion," the same cinematic creed he professed in his cameo role in Godard's Pierrot Le Fou.Fuller is a funny character. He was already around 80, a wizened old man that seems only about half the height of Jarmusch, but he's full of energy and enthusiasm for this adventure. He appears almost invariably with a cigar in his mouth and a baseball cap and talks in this really old-timey New York Jewish accent. I honestly found him hard to understand at points, it's like watching someone speaking Elizabethan English step out into the world of 1992.TIGRERO doesn't seem a major achievement in documentary filmmaking, and after one viewing I don't feel in a hurry to ever see it again. Nonetheless, it was an enjoyable 75 minutes and I appreciated learning something about this part of the world.

... View MoreThe image of hipster Jarmusch and Old-School Fuller wandering around like 2 characters in search of an epiphany was wacky enough. Place them in the middle of a Karaja village, with the amazing back-story of Fuller's flirtation with a jungle epic-that-never-was, and you've got a great little documentary that surpasses expectations--if in fact you had any. It's true that Jarmusch is absurdly out of place here, but that only ads to the surrealistic bent of the thing. And Fuller, a physical midget next to Jarmusch, is the one who is truly larger than life; a throwback to a time when directors truly dreamed and took action--the sort of character that Hollywood, in its increasing dependence on CGI, has conveniently squelched. We get to see a maverick, a dreamer, an egotist and a great observer of life in its myriad forms, who clearly loved every second of his time on this earth. The film is somewhat hampered by a lack of what a script man would call structure. And yet that didn't bother me because it was like watching a human circus unfolding: Here a Karaja ritual; there, Fuller fulminating about what coulda been, and everywhere around the amazing Mato Grosso, the real star of the story. Okay, it's no Aguirre, but if you love the process of film in its purest form, this is a terrific little flick.

... View MoreMuch like their fiction counterparts, documentaries rise and fall with their subject matter. If they are to be successful they must have a story worth telling. This one doesn't. In fact it wouldn't have been made to begin with if Sam Fuller wasn't such a cult icon for these two guys here, Jarmusch and Kaurismaki. In 1955 Sam Fuller was sent to the Matto Grosso jungle in Brazil by Zanuck of 20th Century Fox to gather material for an exotic adventure about an escaped convict woman, her husband and a bounty-hunter, the titular Tigrero. Wayne and Gardner were supposed to star, the film fell apart, apparently no insurance company was willing to take the risk of Wayne and Gardner shooting on location; but not before Fuller managed to shoot footage of the Indian tribe on 16mm. The footage, along with the script Fuller had prepared, languished for nearly 40 years. Fuller returned to the Indian tribe he once filmed, this time with Jim Jarmusch and Mika Kaurismäki, to shoot a documentary on a film that was never made.The major problem of Tigrero is that it is aimless and flaccid. It starts as a humorous travelogue of sorts then digresses in the traditions and customs of the Indian tribe which is only tangential at best and then finally arrives at what the box promised: anecdotal material provided by Fuller himself about the film. Fuller is such an interesting and lively character that he can almost sustain the film by himself, even when his stories are little more than small tidbits. On the other hand, his interviewer, Jarmusch, comes off as a self-conscious, humorless hipster, walking around the huts of the village in his cool Ramones tshirt and Rayban shades. Mika Kaurismäki's direction is average at best, mostly because he seems completely unprepared. There's no angle to the story to hook you with. Fuller's first travel through the Brazilian jungle, carrying with him a 16mm camera, film stock, a box of cigars and a Beretta, an adventure more interesting than the lurid, melodramatic subject of the movie he was supposed to be researching, isn't given its proper due. It's no wonder then that the most captivating scene in the movie, and the one that achieves any kind of emotional leverage, involves the indians watching the footage of their ancestors 40 years later.

... View MoreI didn't find Tigrero: A Film That Was Never Made to be one that worked completely as a documentary, but there was a lot that I did admire about it. The director Mika Kaurismaki (of the Kaurismaki brothers, the famous Finnish filmmakers) chooses to not just plunge the viewer into the Karaja culture, of which Tigrero is mostly set in, but sets up a sort of 'huh' opening scene where director Samuel Fuller persuades Jim Jarmisch to go with him on a trip into the jungles of Brazil for some odd reason or another. I could get a sense of what Kaurismaki was after with this, to make the documentary feel more like a hybrid, like something out of Jarmusch's own Coffe & Cigarettes where the real people are themselves, only still playing characters. But the film really only gets some lift once Kaurismaki gives up on the scripted stuff- which isn't awful but feels like it's out of some other movie- and gets to the facts, the images of total reality and the stories of old. In this case, like with Les Blank's Burden of Dreams, Kaurismaki is almost more interested in the native people of the area, the Karaja, who were there for centuries when Fuller arrived in 1956 to do some 16mm rough shooting of the area for a film he was preparing (of the title here).In fact, I wondered after a while when Kaurismaki would get to the story behind the 'film never made', as he continually shows the Karaja and their customs. This isn't a bad thing at all actually, and there are even a couple of wonderfully strange moments, like the two men doing their chant as their stuck together and go by the cigar-chomping Fuller. Or when we see how the natives do their mating ritual, which involves the men being covered completely by bushes and going around the women, who rub their bellies in hope of having babies. But really, part of the touching factor is just in seeing how these people lived and payed heed to nature, which is their sort of God, however not exactly their God as Fuller observes "they don't know what God is" (he makes a note, however, that Christians don't either, but they just flaunt it more). With all of this footage, either shot by Kaurismaki or Fuller or even through Jarmusch as he carries around a camcorder, it's all very absorbing on an anthropological level, and the history behind the people too is interesting, how the Westerners came into try and modernize, and they almost crushed their culture.Once this is mostly through with we do finally get to Fuller talking about Tigrero, and it's pretty much worth the wait to hear one of the giants of American film in the 50s and 60s (both studio-wise and independent) talk about the ambition of it all, how John Wayne and Ava Gardner would be cast, how it all rung of slight subversion of the action/adventure picture set in exotic locations. It's always a treat too just to hear how Fuller tells these stories, no b.s. involved ever, and how after the crushing blow from the insurance company that the film could not go on (they wouldn't want to put up the millions of dollars in case, well, one of the stars died), how he integrated the footage into Shock Corridor. Jarmusch also makes sure the questions are direct as possible, however with a good level of adoration from an obvious fan, and with his own dead-pan narration telling of the Karaja's stories and the like. By the end, I knew I had seen at least 2/3 of an excellent documentary on a group of people I'd never known before, and had seen things about their ways of life and understanding of one another that was fulfilling, and from knowing another lot of great lost stories by a filmmaker who knew his stuff. If only Kaurismaki wouldn't get in the way sometimes.

... View More