The Jacques Prevert-Jean Renoir teaming provides for an exciting tale of murder, mens rea, judgment and justice. The narrative frame introduces the story through straightforward exposition. Great depth of field and uneven staging/blocking of characters constructs a space unobtrusively in order to make room for the free interchange of political positions of everyday people. It is difficult to deny that M. Lange isn't a call for French citizens to become politicized, but one cannot overlook the contribution of Prevert to that end. Mobile framing is employed once Florelle's character introduces the past events that led her and M. Lange into the provincial regions. The mobile framing operates to connect lives that might otherwise require the conjuring of contrived connections by the audience. The fact is that these people live and work together - that is the essence of their connection, and for Prevert (and Renoir) such a connection is enough to create a demand for respect, dignity and autonomy. Batala throws a wrench in all that good stuff and provides the catalyst for politicization. Is murder condoned in this film or is it representative of the sacrifice that will be made to take up a firm political position? (a massive issue at the time of the Popular Front) M. Lange is all about context but in the most self-reflexive manner. Even the Arizona Jim storyline has a direct conversation operating within the French film industry at the time. M. Lange isn't anachronistic but for a contemporary audience, the concept of group responsibility has distorted and perverted into an amorphous hideous blob cranking up the volume of the latest tech trinket to drown out the screams of a Kitty Genovese in the alley below. This makes M. Lange a refreshing take on politics but a depressing one, given the contemporary spectator has the foreknowledge that WWII happened and that international corporate conglomeration (Batala's wet dream) has become so dominant that an Occupy Movement on Wall Street looks more like a corporate-sponsored Hoedown-cum-Pow-Wow... and just wait for the time management game version to be released on iPhone in the next three months. If M. Lange were real life in 2013 we can be sure that Batala "getting his" would mean getting the highest amount of profit participation and controlling the creative accounting end of things when the box office closes on the film's run. It is beautiful to see a world fighting for what is right. Prevert was unabashed in that regard. Renoir was fighting for something else - both more personal and universal. In a true Renoir film, Batala would have been a more complex character... likely something between King Louis in La Marseillaise and Dede in La Chienee. That is to say, his return would be announced and his escape would be ensured at the expense of some poor bugger's own life... in a kind of reprehensible accident. What does the 360 shot mean to me? I believe that it represents a political statement about the deferral of responsibility. The Lange and Batala roles are a clever reversal of the real issue... where do you stand against the threat of fascism that will soon begin stomping faces (which it did in abundance).

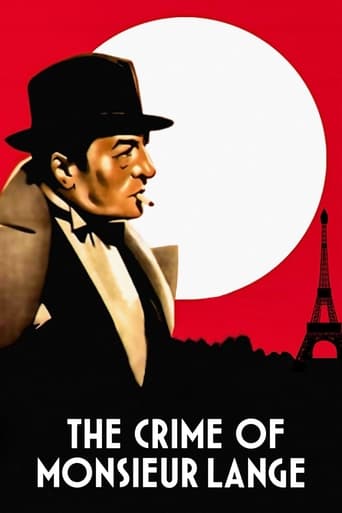

... View MoreOne of the greatest (almost) lost films I've seen is Jean Renoir's "The Crime of Monsieur Lange." Renoir made it in 1936, prior to the invasion of France by German forces, and just before his two wartime masterpieces "Rules of the Game" and "Grand Illusion," which both have overshadowed it critically and in terms of popularity. But I consider "Lange" to be richer in irony, political bite, and even humanity than its more famous followers.It relates the story of one Amedee Lange, a pulp writer for a weekly paper, published by the womanizing and ever scheming Batala, played with delicious gregariousness by Jules Berry. Lange writes the continuing western serial "Arizona Jim" for the paper, but his prose suffers the indignity of having advertising blurbs inserted into it to by Berry. When Berry, in an effort to avoid creditors, fakes his own death in a train wreck, Lange and the other workers for the paper rally and take over the publishing themselves, creating a popular and commercial success, continuing "Arizona Jim," sharing in the tasks and rewards, and even staging a (rather stagy and unconvincing) film version of the western for the local cinemas.Renoir creates a potent political subtext by defining this community - the workers, neighbors, and friends - around a single courtyard. His camera glides through doorways and peers through the windows of apartments and shops to eavesdrop on all the personal and professional intrigues (in a way that at the time was considered outrageously overdone). Lange himself has never been outside Paris, and when people comment on the apparent "authenticity" of his western serial, he constantly corrects them - but to no avail. He is soon taken for the lover of the laundress whom his bed-ridden friend has a crush on, another misunderstanding. Lange's a fake but he barely suspects as much, as he's too concerned with trying to explain, facilitate his friends, or going along for the ride to ever express much more than a sense that he finds the situation ironic. His misunderstood, almost aggressively passive existence becomes the catalyst and center of this self-forming community, a new populist collective that's practically communist.When Berry unexpectedly returns (dressed in a priest's outfit he's appropriated), he intends to reap the benefits of the commune's success publishing and filming the serial. Lange realizes Berry's capitalist worldview and intent to dictate over them again threatens the well-being of the community, indeed will destroy it. After a drunken party that night (in which Marcel Lévesque gives a speech, in a way reprising his role as the good-hearted sidekick in Feuillade's 1917's "Les Vampires"!) Lange leaves Berry's office and the camera follows him outside through the windows of the office. With a bravura camera pan of a full 360 degrees to take in all the elements around the central courtyard (considered quite self-indulgent then, but now practically invisible to our jaded eyes) Renoir returns to Berry, who's now lying on the cobblestones bleeding - Lange has stabbed him off-screen - yet the camera move signifies a profound emotional event has transpired and transformed the community...Lange was made during the period that the Popular Front was gaining political ground in France, when there was optimism that people could band together and conquer the threat that Hitler was manifesting. Renoir's political themes have always been background texture rather than text "The Rules of the Game" is considered one of the best anti-war films ever made and yet the topic is never brought up in the film. Even "Grand Illusion," taking place in prisoner-of-war camps, concerns itself primarily with the class-based relations between the Germans and their captured prisoners.Lange's positioning as the reluctant center and catalyst for the commune, as well as its inadvertent savior (by eventually committing murder, the "crime" of the title), is played in ironic set-ups. Berry is dressed as a priest for his ignoble return. Earlier Berry mentions to a priest on the train he "must be able to get away with anything" and this returning sheep in wolf's clothing is another resonance with how people put up fronts that are misunderstood. The film also manages to address, redolent in its subtext, the vagaries of pop culture, verisimilitude of representation, and personal responsibility. (None of the handful of pregnancies in the picture seem to enjoy the benefit of being in wedlock it's likely that Berry is responsible for all of them).My favorite moment occurs at the train station, when Berry is about to flee the office for the first time. He's saying goodbye to one of his smitten secretaries (who doesn't realize what a cad he truly is). Renoir allows Berry a moment of wisdom as he tells her how to capture the sympathies of some passing young man (speaking perhaps from personal knowledge) so she won't be lost, abandoned, once he leaves her - by suggesting she pretend to cry over a departing lover on the station platform. Indeed, as Berry's train leaves, her sobs capture the attention of a passing man, whom she begins to walk with. The shot fades out with the hint of a slight smile on her face as she begins to warm to her new conquest. Amazing.Truffaut called "Monsieur Lange" Renoir's greatest work. The film was issued by Interama on laserdisc in 1988 (now way out of print of course). It was recently issued on VHS from Kino, now OOP as well, and could use a Criterion-grade upgrade and reissue.

... View MoreIt takes a while to locate one's bearings in this work, although that speaks to its emotional and thematic complexity. The film has the constant pace and vivacity and glee that is (stereotypically?) associated with Renoir - the film is something of a romantic whirl, with the interconnections of men and women are beguilingly dramatized in all their fleeting glory. Even the scenes with the wicked boss have an initial joie de vivre. Lange himself retains a restrained calm at the heart of it all - until he comes to illustrate the normal man who takes a desperate, self-sacrificing stand for the good of others. Although idealistic, his action resonates when offset against the explicitly cartoonish heroism of the Arizona Jim character (which we see embodied in some epically corny tableaux), and the impact thrives from being based in a muscular evocation of left-wing collectivist sympathies (a strand that comes over heavily in the almost idyllic scenes of things after the demise of the capitalist - with workers happy and lovers unfettered; although I found the very end of the film a bit puzzling).

... View MoreThis very simple movie is not Jean Renoir's best, but it shows some very interesting social issues, typical of the 1930's french movement of cooperative togetherness. In this film, a very bad man (Jules Berry) steals the workers of his journal, seduce innocent girls and don't pay his debts. To run away from the police, he pretends to be dead. Then, the workers of the journal forms a cooperative and had big success, until the day the bad man come back. Renoir's direction is just good, but the actors seems to improvise.

... View More