The filmmaker has been granted access to the "inner circle" (for no apparent reason), and Richer, his coworkers, employees, his wife etc talk to her quite casually, almost as a friend. But she does not take full advantage of this opportunity. There are no intelligent conversations, only friendly conversations. That is not enough. It is okay that Richter does not want to talk too much about personal matters, and does not really open his bag of tricks as a painter (in front of a running camera). Being filmed at work prevents creative powers being set free, many artists say (e.g. I remember Horst Janssen saying this to a film-team). Sometimes Richter seems to expect more of the conversation but quickly realizes that no-one around him has anything valuable to say about his art. Seems to happen all the time, so he does not care. He is not a diva, but quite down to earth.It is honorable that the writer/director does not want to lecture the user, this also means almost nothing gets treated with sufficient depth. I suspect the writer does not know enough about art (despite a lot of research and effort that she undoubtedly put into this documentary), and so has no intelligent questions to ask when it matters. Even when the conversation does not revolve around art, but instead abound family (for instance) the dialog is a but more fluent, but still, it stays quite boring.Sometimes the filmmaker throws in some snippets from vintage documentaries from the 60s which are a bit more inquisitive, but they seem misplaced and thus are not really helpful either. There are only subtitles shown very briefly. The music is minimalist modern classical (piano solo, or strings).If you praised Richters greatness as a painter to someone who does not know anything about him, and you showed her this movie before you showed her any paintings of his, she'd never believe that this is one of the greatest painters of our time.

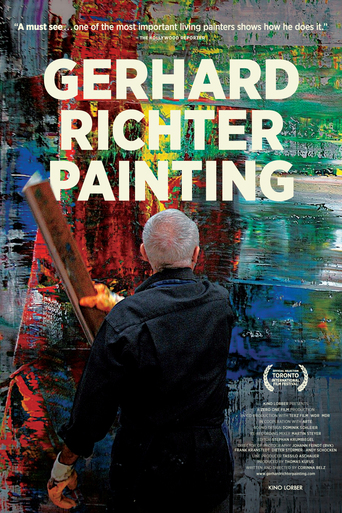

... View MoreThe only reason I gave this film 9 out of 10, was because I believe Corinna should have invested in a roller for her tripod. Would have made for less shaking in the videos of Richter while he is painting. As a documentary filmmaker and painter myself. I can fully understand and admire what Ms. Belz accomplished in this film. I do however, remembering seeing the film this past Friday, note that I wish the lower 3rd titles had been a bit bigger for those who wear glasses. I know it was OK for me, but i'm sure a number of people were always asking... "who is that?".I can truly admire this historical document on modern painting. As Richter is not a "post" anything. He is someone who is dedicated to making what he feels is the best work he can do. You will see that in the sections where Ms. Belz speaks with Richters assistants. What they say rings true with many many modernist painters who will have to sit with a work for months before they feel it is ready to be put out in the world.So glad this film is out in the world. I can't wait for the DVD. My only sadness about the DVD is that I don't have the equipment to watch it in the format I first viewed in. This film deserves a big screen.

... View MoreGerhard Richter is an old man who doesn't like to be interviewed, who doesn't like to be filmed and who doesn't like to talk about his paintings. He's also a very famous German artist and though he obviously couldn't care less about this film, some clever marketing executive said, hell, we do it anyway, cause he is so damn famous, once this film is out, the middle class intellectuals will flock into the cinema in order to feel sophisticated in the virtual presence of a true artist. Sadly enough, judging by the crowd it attracted when I went so see it, it worked pretty well. My main gripe with this film is that Corinna Belz, who I take to be some TV journalist, has no concept for this full length documentary. Apparently she was under the illusion that it's enough to just stumble into the studio of such a genius, turn on the camera and then the magic will unfold. Well, sadly enough, it doesn't. In fact nothing happens and Corinna's inane off camera questions (How long did it take you?) don't help either. But then she is not bold enough to concentrate on the one thing that does in fact happen, namely, Gerhard Richter in the process of painting; no, spoiled by television aesthetics the edit never lingers too long on the act itself but feels compelled to jet to New York and London for a more cosmopolitan flair. But whenever I was on the brink of nodding off I was jolted back to attention by archive footage from the sixties where an eloquent and rather angry Richter is talking about his approach towards art. That would have been the proper time to make a documentary like this. Back then when he was still able to express himself coherently, when he was on the peak of his artistic powers, when he wasn't the weary and rather tired superstar he is now. Another venerable approach would have been to actually tell us something about his art, his significance in todays art world, but no one here has the guts to do so. He created so many great paintings, but this film doesn't do him any justice. He apparently wants to be left alone in his studio so that he can concentrate on his art. Whatever happened to decorum in the film industry. Just because he is old, doesn't mean his wishes should be ignored, especially when the resulting film is as nondescript as this.

... View More* Contains spoilers *Arshile Gorky's wife reported, when he was still working in his New York studio, that she would see a canvas in one state, and, by the time that she awoke, it had been worked upon so much that it was largely unrecognizable. There are elements of this in what Gerhard Richter seeks to achieve in spite of the presence of those filming him at work, but that is the territory of this kind of work, and, really, it ought not to be too surprising (to which I shall return later).Rather than wondering, rather pointlessly, whether Gorky would have allowed director Corinna Belz in when he was working, I can only profess admiration for Richter that, despite the fact that it was putting him off, he did not close down the access. That said, whether he would have welcomed – or, if given the choice, approved of – the temporal juxtaposition of how what he was working on looked at different moments, I do not know.What I do know is that he loads the squeegee with paint, and then has to say that what he was about to do cannot be done then, because it will not succeed. Whatever Richter may 'really' be like, he gave the impression on camera of being a sensitive man, and he seemed unnerved that he had started preparing for something that was not possible, and which, one would like to think, he might not have done, if he had felt at ease. He did not, not when trying to work on his canvases.Indeed, following on from that, if we invest an artist and his or her work with worth, then we have to leave him or her free to decide when a work is finished, and what is effective and what is not. And yet I am imagining that the moment when he white-washes over a grey composition may have left some who watched the film wishing that he had left it untouched: I can understand that, but I take the different view – that he created it, and he must be satisfied with it, if it is to bear his name.His assistants, his wife, recognize the knife-edge on which the creative process is balanced at this stage, and say that, if they were to comment that they think that something is right as it stands, what they have said would be more likely to cause Richter to re-work it. Not out of perversity, I fully believe, but because, as the camera and crew do, the remark would interrupt and subvert the process.Unlike artists who have their studios, and would, throughout history, delegate tasks to assistants, Richter's was shown getting the paint ready, but the artist himself was even cleaning off his materials at the end of the session. He was, as he several times expressed in response to questioning (some of which was better and more artistically minded than other parts of it), clearly finding his way with the works, and we were told about how their current state had to stand up (as if to scrutiny, scrutiny of a most honest kind – and Richter believes in truth in painting) for several days: white-washing over was not something over which those in his entourage could regularly afford to be regretful.As I say, the creation is the artist's, and he or she is the one to find a way ahead. In the case, for example, of Joan Miró, he had the luxury of being able to re-work canvases decades later that were still in his possession, whereas the Tate refused, I think, Francis Bacon, access to some of his, because it did not want them – as it owned them – any different from how they were, and knew that that would be the result otherwise.One observation, amongst many intelligent things that Richter said about his work (and it was also fascinating to see him about the business not only of planning out exhibition spaces in 1:50 scale, but to hear him pleading with photographers at the opening of a show who required just one more pose that they had so many shots already), was that a painting makes an assertion that does not bear much company: in the context of having to hang several pieces on each wall, and plan it all out, that seemed just as much a challenge as in the studio, with canvases making differing assertions in different ways about how they should work.So the supremacy of each work's voice, its statement, and, I would say, for the painter to decide what it is to say and when it is saying it. Then, for Richter, what he said that he valued was people adopting the attitude of those attending a gallery in New York, who would more freely, more honestly, say that they liked this group of paintings, but that the grey compositions were terrible. The point that he was making is he does not feel the polite comment that something is 'interesting', to which he is usually exposed, is that kind of genuine response.As for me, I'm looking forward to spending time at the new exhibition at Tate Modern – and maybe to watching this film again there during the time that it is on.

... View More