Okay, so we expect a certain clarity from cinema about the conundrums of life. In Ozu this appears in a combination of things. The spatiotemporal eye is empty, grounded, it's a dispassionate awareness that sets the room for life to play out. It's more than realism, it's a way of creating realization about the point things are more sensibly viewed from.Narrative then is a matter of having something to view. Here several things blend. Officework for the salaryman in the audience. War reminiscence. A marriage grown distant to illustrate the tension in the home. So each of these threads poses an aspect of life, the idea is that life also extends a bit in this or that direction. This is the opportunity to create that realization that in the first place informs the passage of time. It's not that things were better in the old days, this is never the point in his films. Viewers who miss this are stuck with a sentimental uncle. It's that things are not different, that slightly changed the same conundrums repeat: salarymen are not more distinguished than the old craftsmen, husbands will stray as before and so on. In the same swoop it creates both melancholy and a certain kind of relief.Ozu is quaint then in this sense of being content by the way life envelops and figures itself out, letting the drama peter out as a way of saying it was never worth being caught in. This was most elegantly seen in Early Summer in the girl's spontaneous decision one night to marry. Here the wife in the end makes her choice to follow her husband in his transfer, not because anything has been solved, but because it is now seen to not matter.But he removes the self from the camera only to put it back in the characters. This is a great and difficult balance that to my mind he only accomplished once or twice, how little to show and say. There's no precise answer, just different brushstrokes to try. Push with a little more force and it becomes a moral smudge, push less and maybe there won't be an intelligible trace.Ozu traces faintly the turmoil but too hard the worldly lesson, it seems every minor character is encountered to offer advice at some point. It defeats the whole point of a world that is not yet figured.

... View MoreI consider Yasujiro Ozu one of the worlds most significant and distinctive directors, a man who eschews false dazzle in favor of examining the human condition, human relationships; most of his films are quietly incisive portraits of people coming to conclusions and making decisions which will permanently affect their lives. Ozu imparts subtlety to his characters, his sense of time and place are impeccable, and his respect for his characters unparalleled. All of that said, I think that Early Spring is one of his least effective--one easily sees the point he makes about corporate behavior and marital infidelity, but this one, rather than quietly contemplative, struck me as merely slow. The characters too often lack any redeeming qualities, and yet we are apparently supposed to care about them for more than two hours, difficult when there is so little to work with--Early Spring is certainly not a stinker, by any means, but for me, a lesser Ozu, and if you want to start with something more characteristic, begin with either version of Floating Weeds, or with his masterpiece, Tokyo Story.

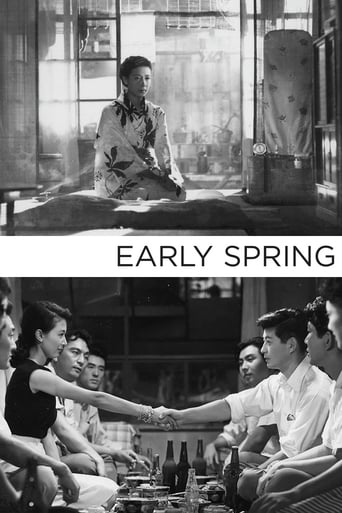

... View MoreEarly Spring came between Ozu's incredible masterpieces Tokyo Story and Tokyo Twilight. No surprise then, that it kind of falls flat in places. It's by no means a bad film, but it adds a bit too much complexity, making the focus confusing at points. The film starts as a comment on the salary man. The opening scenes are both funny and sad, as we see the empty streets of Japan gradually fill with men and women in white shirts. They all come together at the subway station, and then we see two men in an office building looking down at the madness below. These are the kind of details one must love about Ozu. It is all represented there on the screen, and without many words we know what is going on. As the film continues we see the workers on their breaks and finally arranging a weekend trip. On this trip is where the real story begins. A young married man named Shoji is attracted to a young girl nicknamed "Goldfish". They are unable to hide their attraction, as their colleagues start spreading rumors and noticing the smiles between the two. Eventually they give into their temptation. It's the effects after this betrayal that are the key focus. The young girl is surprised that she develops emotions, while Shoji is instantly ashamed of himself. His guilt soon grows, and he avoids his wife. Because of this his wife begins to suspect he is cheating on her. The film shows how destructive guilt can be. As Shoji tries to keep his mind off the affair, he ends up forgetting the anniversary of his son's death. The film is too long for its material. There simply isn't enough going on in the middle, and too much at the beginning and end. What it does offer is Ozu's look at relationships without the arrangement of a marriage. Instead, this shows the hard work and commitment a marriage takes. A theme that was handled a lot more competently and economically in his next feature.

... View MoreSeeing this film is more like looking at a photo album than watching a movie. Characters seem to walk in and out of set scenes, speaking while in the set, and then it is on to the next photo. Some concession need be made for a black and white film from 1956 and for the style of Yasujiro Ozo, yet this approach to film making seems to destroy the continuity of the film. For example, one jumps from tones of Japanese industrial society (340,000 office workers in one city) to hiking on a highway to sitting and drinking tea. This may in fact be the thread of industrial postWWII Japan, but it seems not the fabric. The result appears to be a lack of a coherent Japanese identity, for costumes and jobs appear not to be enough to transcend the disruptive nature of the editing. Ozu is the master of the set scene, but the editing appears disjointed rather than cohesive. There also seems to be a dependence on American stage production rather than Japanese movie making. One cannot help be see a relation between this film and the stage plays of Tennessee Williams and of Arthur Miller. I seem to get the feeling I am watching a Japanese docu-melodrama in Italian neo-realism. I half expect to see Burt Lancaster leap into one of the scenes. The Left Elbow Index considers seven variables of film--acting, film continuity, character development, dialogue, production sets, and plot. The acting is average since there seems to be little more to do than sit and talk. The film continuity is also rated as average, despite the what seems to be disjointed action and time. The character development and plot need help. There is little verbo-robots can become, and the plot of infidelity in marriage seems always to follow the same course, with minor personal variations. The production sets are rated average since in black and white most sets are simply degrees of gray. Average is the rating given to the dialogue. It is functional but appears to lack insight. The best line is "Babies come quicker than raises." The artistry rates average, again color would help, as it does in Ozu's THE END OF SUMMER. The overall LEI average is 3.83, raised to 4 in tribute to Ozu's reputation, which equates to a 6 on the IMDb scale. I recommend the film, it is worth watching as an integral part of film history, keeping in mind that the best of Japanese films have not yet arrived in 1956.

... View More