Director Rolf de Heer who also created another classic aboriginal cultural issues flick, Ten Canoes 2006 plus other classic flicks, Bad Boy Bubby 1993 and Dance Me to My Song 1998 has created another gem in Charlie's Country.Starring David Gulpilil who has been in other classic aboriginal cultural issues flicks, Walkabout 1971, Rabbit-Proof Fence 2002 and Dead Heart 1996 and other classic flicks, Mad Dog Morgan 1976, The Right Stuff 1983, Dark Age 1987 and The Proposition 2005.Also starring Luke Ford who has been in other classic television series, Bikie Wars: Brothers in Arms 2012 and a series of Underbelly 2008-2013.I enjoyed the realistic portrayal of day to day life.If you enjoyed this as much as I did then check out other classic aboriginal cultural issues flicks, Mad Bastards 2010, Mystery Road 2013 and Toomelah 2011.

... View MoreThis movie provides an insight into a world that is difficult for many people to see or understand. The film is beautifully shot, and the scenes and sounds of Australia are magical. The acting is first rate, and the script is very clever. Many of the things Charlie says to European Australians don't make much sense, but in this movie we are able to understand what Charlie is thinking when he says these things, and so we understand perfectly what is meant by every sentence he utters. The sense of longing, and of loneliness is palpable, as is the passionate love of country. The dance scenes with the children are uplifting and lovely. This is a moving and beautiful film, and a huge bridge for building understanding and empathy for a different and valuable culture.

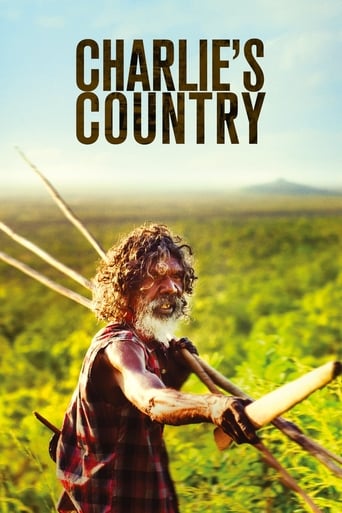

... View MoreAboriginal Australian dancer David Gulpilil has appeared in a number of movies over the years: "Walkabout", "The Last Wave", "Crocodile Dundee" and "Rabbit-Proof Fence" are among his most famous roles. His performance as the titular character in Rolf de Heer's "Charlie's Country" might get remembered as his most important role. Gulpilil plays a Yolngu man living on a reservation with a collection of other Aborigines. Even though the army doesn't enter the area to mow people down, it's still impossible for the people on this reservation to live traditionally, as the police confiscate any possession deemed to be a weapon. So then Charlie decides to move out into the bush to live how he wants."Charlie's Country" will likely be the only Yolngu-language movie that you will ever see. In fact, it's the first movie that I've ever seen spoken mainly in an indigenous Australian language. The presence of words adopted from English is an ever present example of how much Australia's white population has impacted the indigenous population.The movie should serve as a reminder of how Australia's indigenous population lives. Once the island's only inhabitants, they're now 1% of the country's population (but 40% of the prison population). Unemployment and alcoholism are rampant - Charlie even mentions how the white people introduced alcohol and ganja to the Aborigines - and it was only in the last decade that Australia's government offered an official apology for stealing Aboriginal children to get raised as servants for white people. Really good movie.

... View MoreCharlie's Country has a lived-in lead performance, complimented by clean photography, but does the film's love for its central character diminish its ideological objectivity? The socio-political issue the film takes aim at is the restrictions brought upon by "the invention" or the Northern Territory National Emergency Response. Charlie (David Gulpilil) is living in Ramingining, an indigenous community in the Northern Territory, which is a dry area. Charlie is pestered for his welfare payments by his relatives in the area. Although he provides for people, he feels suffocated. He wants his own place, away from all his relatives, but he is told he already has one. He is also frustrated by the restrictions imposed by the local police (one of which is played by Luke Ford). Charlie decides to return to traditional living in the bush. Not only does this make him extremely ill but it also leads him into a new destructive life path while his friends have either adapted to the modern world or they are dying. It takes great sensitivity to write or film a story about cultural problems in any country, given the delicacies of these discussions and the emotions they evoke in people. One can only imagine the difficulty of approaching this subject as an outsider. For a Dutch-Australian filmmaker, who moved from the Netherlands to Sydney when he was eight years old, Rolf de Heer has done remarkably well to make several films about Aborigines. Charlie's Country marks the third part of his indigenous trilogy after The Tracker and Ten Canoes. Each of these films has starred David Gulpilil and although this film is not an autobiography it does contain some biographical elements of this gifted but troubled actor. David Gulpilil has said it is "authentic to my experience of these things". It was his history with alcohol and violence that launched the concept for the film. De Heer visited him in gaol and decided to provide Gulpilil with a film project that he hoped would save his friend from self-imploding. The film's script is co-credited to Gulpilil himself and this has made Rolf de Heer conservative in his approach to the subject matter. Partially a redemption story, the film argues against the restrictions placed on the community by adopting Gulpilil's own values and viewpoint against colonisation. Rather than looking at contextual details like why the alcohol restrictions are emplaced, the film focuses on the lack of money, the poverty and bans on alcohol and traditional methods in these communities. What is troubling about the film is the simplicity of many of these arguments. One example is when Charlie's unlicensed gun and spear are confiscated from him by the police. "I'm not a recreational shooter. I'm hunter", he argues. Would the situation be different for any white person using an unlicensed weapon? In reflection, it is also an uncomfortable scene given that in real life Gulpilil was charged for wielding a machete in a confrontation before being acquitted. By focussing dominantly on the welfare payments and poverty, the film forgoes an opportunity to show the destruction of alcohol in these communities. Surely the burden of alcohol is part of a universal mirror that could be held up to all Australian societies today. Using a moderately light tone, the subject of intoxication is approached through comedy. Some of the film is quietly funny. One gag shot frames Charlie and his friends drinking in front of the alcohol prohibition sign so they can't be punished. Simultaneously, isn't the joke also soft- peddling the seriousness of the issue? The most damaging of any alcohol related crimes in the film is when Charlie buys grog for a black woman who has been banned from drinking. Out of anger he smashes the windscreen of a police car. Gulpilil's own alcohol related crimes were domestic related and more serious and violent. He served time in gaol after he fractured his wife's arm by throwing a broom at her. When de Heer visited him the director said that he was looked after. The film's version of his incarceration isn't subtle. It lunges desperately for our sympathies. The prison sequences starts with a medium close-up shot similar to the Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket where Charlie has his head and beard shaved off, followed by repeated images of slops being served and the camera scanning pedantically over the top of a barbed wire. Yet if there is any reason to see the film it is for Gulpilil's performance which is the cornerstone of the entire story. Using his background and the autobiographical details, he completely dissolves into the character but also shows us just how effortlessly he can inject humour and emotion onto the screen as well. He is an engaging presence and undeniably talented. He is also one of the reasons why the film is never short on personality because the decision to have long shot durations and unbroken takes is mostly justified by his purposeful facial expressions. We can see the internal conflict as he watches other people sink by him, forcing him to reconsider his future. I would have liked to have seen this fine performance attached to a less compromised film though. Although the ending features a beautiful dance it is also merely a short-term resolution for Charlie's problems. Nonetheless, perhaps the very sight of this actor taking his opportunity with both hands will be the most significant message for anyone watching this film. A life salvaged, temporarily, by art.

... View More