For a film about Christian missionaries, this one verges on Horror. Not for the weak of heart--or stomach. One glaring mistake was a veneration of St. Joan of Arc. This film was set in the early 17th century. St. Joan wasn't canonized (through the efforts of Therese of Lisieux later sainted herself, among others) until 1920. There are some theological problems, but they have nothing to do with the film itself and everything to do with the way Roman Catholics chose to present the good news of eternal life and how they chose to describe the afterlife--or their lack of description based on ignorance. Too, when you are baptizing someone who is dying, wouldn't you want to speak their own language, especially if you are fluent in it, instead of Latin--which isn't even your native language? And why are you whipping your back with a rough pine branch until it bleeds after lusting for that Algonquin girl when a simple 'I'm sorry, Jesus. Please give me the strength to fight temptation and to remember that I am celibate by choice so I won't be weighed down by earthly matters' would be far more effective? All in all, this film stands the test of time, and I only give it a 7 rating because of the Joan of Arc mistake and because of the unnecessary rambunctious copulation scenes.

... View Morea film who escape from classic formulas. and the result is a honest image about Amerindians and Europeans and their relationship. the heart of this relation - the profound solitude who defines the Jesuit priest who believes in his mission in few moments more than in God and the natives Canadians for who the danger against their life style is ambiguous. clash of civilizations, it is one of the most touching and clever films about this theme. Lothaire Bluteau does a splendid role, exploring the vulnerability and the faith, the need to help the other and the conscience of sacrifice. the images are amazing. the mixture of sex, violence, pieces from old religion is more than beautiful or convincing. but the great virtue is the precise courage to give a honest portrait of the characters.

... View MoreI saw this film the year it came out. At the time, I was representing the administration of New York Governor Mario Cuomo in conducting relations with the Haudenosaunee, particularly the Mohawks of Akwesasne. Having grown to respect and admire the resilience and determination of these remarkable people, "Black Robe" made a big impression on me.I spent a little over two years (1990-1992)engaged with the Mohawks settling the issue of providing for their public safety needs and negotiating a state/tribal casino gaming compact. Both of these initiatives ultimately ended successfully. The process of developing an indigenous public safety force involved multilateral discussions involving the Mohawks, New York, Quebec and Ontario. It was interesting to me how many of my colleagues had seen "Black Robe" and agreed that it was a beautiful and fairly accurate depiction of history and cultural frictions that persist to this day. To those of us sitting around the table, "Black Robe" gave us a sense that we were playing a meaningful part in a long and fascinating history of the meeting of cultures and hard work that goes into creating a relationship of mutual understanding and respect.Terry O'Neill, Esq. Albany, NY

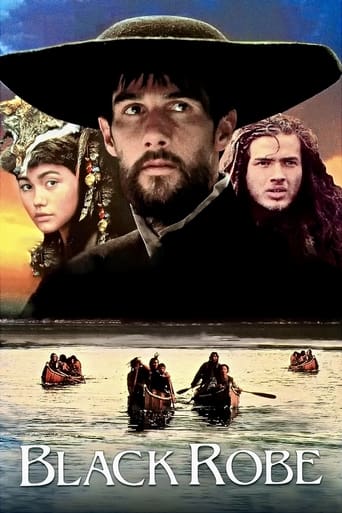

... View MoreIf Bruce Beresford's 'Driving Miss Daisy' suffered from a softened, Hollywooden view of history and racial conflicts, the bleak, beautiful sometimes horrific, always uncompromising 'Black Robe' is its correlative opposite.Set in the 17th century, both the Native Canadian people, and the French Jesuits who come to bring then religion (when they already have their own, thank you very much) are presented as deeply flawed, cold and cruel at times, blind to the complexities of each other's humanity.Yet both are also touched by moments of kindness and understanding that lead to the sense that this story of one Jesuit's torturous trip with a band of native guides is not without it's growth for all involved.Most critics were mixed on this, and I understand their objections, though I don't share them. The film is distant emotionally, and we never really get inside any of the characters, even the titular priest, called 'Black Robe' by the native people. The film is more illustrative than dramatic. Again, the exact opposite strengths and weaknesses of Beresord's 'Driving Miss Daisy', which was full of wonderfully moving characters, but lacking honest context.But I found the historical context here, and intellectual insight, the suspense inherent to the story, along with the physical beauty of the locations and the sharply honest insight into the Native universe enough to be always engrossed and interested, and ultimately quite moved.

... View More