As a big fan of Antonioni's films ("Blow-Up" is one of my favourite movies of all times, one of a very few of his which have not dated over the years), I just had to see "Beyond", albeit almost 20 years after it was made.Well, I watched it for the fantastic cinematography, the music, and Antonioni's famous attention to visual detail . As for the stories, they are disjointed, quite pretentious, and seem to be just a pretext to show the beauty of the actresses. I was also disappointed by the predictability of the final story (with Irene Jacob) - I think most viewers would guess early on how it was going to end.

... View More"You love only when you're after something inaccessible; you only love what you don't possess." - Proust Michelangelo Antonioni wrote "That Bowling Alley On The Tiber" in the mid 1980s. Despite being a compilation of disparate short stories, the book contained a single overarching narrative; that of a director who constantly collects images, with an eye toward spinning these images into films.Misperceived as a collection of disconnected short films, Antonioni's "Beyond The Clouds" tells the same story: the tale of a director who collects - and works simultaneously forwards and backwards from - images, investing them all with content. This act of an artist conjuring art out of absence, of imbuing images with fantastical pasts, presents and futures, then becomes Antonioni's metaphor for "love". Love, in other words, is illusionary, and is always defined by the visual imagination.Cast because of his resemblance to Antonioni, the film stars actor John Malkovich as a wandering film director. Opening shot: Malkovich floating through clouds, entering a dream space. The artist then spins these clouds into the misty streets of Italy. Here he speaks of the "vital impulse" which "drives life", and "deceives us into creating pasts and futures". He then picks up a camera. "Reality exists behind the image," he says. Typical of Antonioni, the film's dialogue has a metaphysical twang.Malkovich then takes a photograph of a street. From this image he will conjure a story. The film itself consists of numerous stories nested within stories, all of which are spun from things Malkovich sees and all of which charter the disintegration of love's myths.The film's first story involves an ultra beautiful young man and young woman. Later the young man will conjure the woman up whilst gazing out a hotel window. The hotel is shrouded in fog and water. Hypnotically, incessant traffic flows in the background.The couple talk: "We all want to live in someone's imagination," he says. Earlier he spoke of mankind's rise in disenchantment. Love, Antonioni implies, is an enchantment that continues to survive. He loves her, he then says, because her eyes are empty, free to be filled by his idealized brush. But their wants are impossible. They retreat to separate bedrooms and fantasize about each other. The film is about the closing of the gap between those two bedrooms. He conjures her up again after watching a film. They speak, every line about objects being perverted; scents, eyes, coffee leaves which give off signals. Every part of the body is an object to be invested with story; fetishized by the mind's eye. They then climb a flight of stairs up to her apartment. He stands before a window (note the use of windows, elevators, stairs etc throughout the film). He wants her, but can't touch her body, forever separated by a certain gap. From a window, she watches as he leaves.Malkovich reappears. He studies a beach photograph whilst himself at a beach (reflexively linking masculinized cameras and eyes). From this photograph he spins the tale of a young shop assistant whom he becomes infatuated with. Cue the best "eyeball sex scene" (it's a metaphysical rape!) since "Barry Lyndon", in which a scrumptiously sleazy Malkovich enters the young woman's shop and oozes desire. "Can I help you?" a second woman asks. "Just looking," he tells her. In a brilliant bit of casting, she's played by Antonioni's own wife. Antonioni/Malkovich then rejects his wife and fixates on the younger woman who, realising that she's the property of his fantasies, grows horrified. She poses at a window as he leaves. Later she tells him she's a murderer. Having confronted the tainted image beneath the fiction, he can now touch her. While the film's first sex scene stresses distance, space, this one stresses contact, flesh on flesh, ugliness and beauty co-mingling. He leaves her standing longingly at a window. The film's subsequent short stories echo in innumerable ways what we've previously seen, each investigating the gap between desire and attainment, imagination and reality; what the enchanted eye and camera take in, the flesh can't hold. As the gap closes, the couples then literally fall apart (apartments stripped, vacated etc). Women, meanwhile, increasingly fight back and start defining how men see.Unique amongst these stories is one in which an elderly couple discuss the pitfalls of postmodernism and its aesthetic of nostalgia - an era in which artists replicate the work of others is thus tied to love/sex, all of which are desires to nostalgically resurrect and hopelessly merge with "dead images" - and a story about a woman who has unconditionally given herself to God. Thus the film's subsections charter a movement away from awkward first love, to erotic sex, to disillusioned, nihilistic sex, to post-sex old age and contentment to celibacy or spiritual abstinence.Ultimately, not only is love Nothing (and, paradoxically, the underlying Everything), a gap which cannot be filled, but it is always linked with violence, power, possessiveness, and narcissism. Selfishly, it is one's own ego one loves when "in love". It is one's own ego made real on the imaginary level, as "to love" is "to wish to be loved". A polymorphous perversion, love is a deception involving giving what one does not have. What is "truly sought" in love is thus something experienced as painfully missing from one's life: some comforting sense of absolute belonging and acceptance, love's desire masking a more hidden desire: to gain some control over our own helplessness. Thus true love is to want nothing of someone.For Antonioni, there is something at the heart of sexuality that doesn't work. While sex is the act through which we hope to reduce or cancel desire, "love" is an insatiable dysfunction. All objects are unsatisfying because there are always other objects. Paradoxically that unbridgeable gap, that inevitable disparity between desire and its object, is what forever drives/inspires man.10/10 - Moody masterpiece.

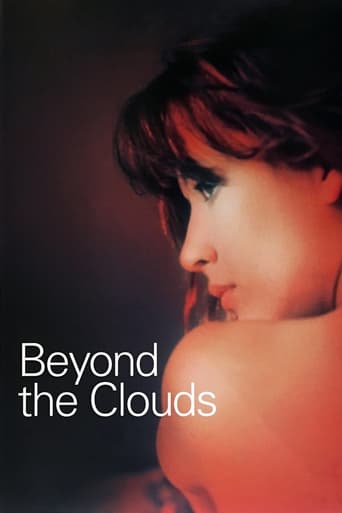

... View MoreIf you speak French or can put up with sub-titles, you will really enjoy this movie. If on the other hand you just want to see God's most beautiful creatures, this is a must see. Not an ounce of silicon in sight. Zalman King eat your heart out. Sophie Marceau's body is the epitome of perfection and everything I had ever fantasized about. Her part is even in English. Even the fact that she was nude with John Malkovich did not detract for her beauty. Sophie is a ten if ever there was one. Chiara Caselli and Inés Sastre are 9.5s. Oh yeah, it is a pretty good story. Several little vignettes are woven together in a sort of Six Degrees of Separation style.

... View MoreThis is a special film if you know the context. Antonioni, in his eighties, had been crippled by a stroke. Mute and half paralyzed, his friends -- who incidentally are the best the film world has -- arranged for him to 'direct' a last significant film. The idea is that he can conjure a story into being by just looking at it. So we have a film: about a director who conjures stories by simple observation. And the matter of the (four) stories is about how the visual imagination defines love.The film emerges by giving us the tools to bring it into being through our own imagination. The result is pure movie-world: every person (except the director) is lovely in aspect or movement. Some of these women are ultralovely, and they exist in a dreamy misty world of sensual encounter. There is no nuance, no hint that anything exists but what we see; no desire is at work other than what we create.I know of no other film that so successfully manipulates our own visual yearning to have us create the world we see. He understands something about not touching. No one understands Van Morrison visually like he does. Morrison's Celtic space music is predicated on precisely the same notion: the sensual touch that implies but doesn't physically touch.Antonioni's redhead wife appears, appropriately as the shopkeeper and she also directs a lackluster 'making of' film that is on the DVD.Ted's Evaluation -- 3 of 4: Worth watching.

... View More