I lived above James Booker in the French Quarter on Dumaine Street in New Orleans in 1983 and one morning I came downstairs on my way to work and saw him standing in front door of his courtyard apartment and he asked me to call him am ambulance. That night when I came home the door to the courtyard was wide open and I somehow sensed the inevitable. I walked over to the french doors of his apartment, peered through the glass. All was quiet but I remember seeing his hats and canes on the wall right in front of me. I found out soon after that he had died that day. His music is exceptional and will send a lightning bolt through you the second you hear him sing and play his first note. Soulful and yearning, the circumstances of his life molded him and we get a real sense of who he was in this film. The effects of his music is immediate and Booker is a dynamic presence. I don't think I'll ever love a piano player more than James Booker and am forever enriched as I recall his sound, electrifying, soulful and grabbing at your heartstrings. How wonderful we get this glimpse into his genius that is so important to remember and pay tribute to.

... View MoreThe fact that this has still not found a distributor makes me worry about the future of the medium. I can honestly say that this is among the greatest documentary films I have ever seen (and I've seen A LOT). James Booker was such an extraordinary character that even a so-so filmmaker would be make something able to hold your interest. Fortunately for us, it comes from a director, Lily Keber, has the potential to rank alongside the undisputed greats such as Errol Morris and Werner Herzog. The only thing that seems to be standing in the way is the fact that there is (as of yet) no distributor. The recent wave of music documentaries spotlighting lesser known bands and musicians ('Searching For Sugarman, A Band Called Death, Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me, etc.) makes this one a surefire hit. GET ON IT!

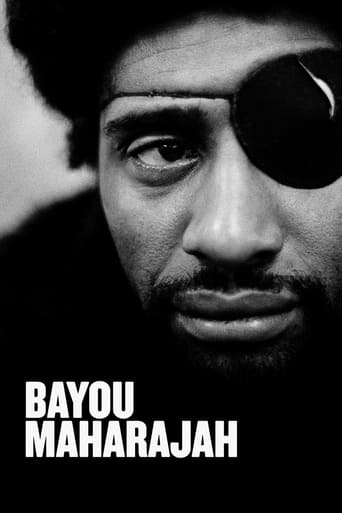

... View MoreIf you weren't looking for it, it was easy to miss the L.A. premiere of Bayou Maharajah, Lily Keber's magnificent new documentary about the New Orleans singer-pianist James Booker. It appeared at Outfest, the local LGBT film festival. At this point, it may be the only screening the picture will receive locally for some time: It still has not secured theatrical distribution. But it may show up at a film festival in your neck of the woods.Even the most radically sensational aspects of Booker's life – his alcoholism, his addiction to heroin and cocaine – get measured treatment. One violent piece of Booker's legend – the loss of his left eye – receives widely divergent retelling from a host of witnesses, none of whom appears to have the real story. Every element of what could have been a luridly told tale is recounted even-handedly, with the heat turned down low.The focus of Bayou Maharajah, as it should be, is on Booker's extraordinary music. He was a pure product of New Orleans, where he was born in 1939 and died, at the age of 43, in 1983. He stands in a line of Crescent City piano wizards that includes Edward Frank, Tuts Washington, Archibald, Professor Longhair, and Fats Domino, to name just a few. Jelly Roll Morton was clearly a model of sorts. But Booker's style, though rooted in New Orleans jazz and R&B, was sui generis. Perhaps that is why he still remains one of the city's least-known giants. The fact that he cut just two studio albums in his own right during his lifetime – Junco Partner (1976) and Classified (1982) – may have something more to do with his comparative obscurity.It's a pity, for Booker is beyond compare. Reared in a family of Baptist ministers, he learned piano and organ (and saxophone as well) as a child, and showed prodigious skill on the keyboards. He was as at home with the classics as he was with the funk. He was just 14 when he recorded his first hit, "Doin' the Hambone," for Imperial Records. A No. 3 R&B hit, "Gonzo," followed in 1960. But his own preferences turned to hard drugs, and he wound up, in his words, "partying on the Ponderosa" – doing a stint at Louisiana's notorious Angola prison farm.Booker had opportunities to record – the master tapes of a 1973 album cut with Dr. John's band disappeared after he absconded with them for "safe keeping" – but he found his greatest success as a performer on the European festival circuit.After his Montreux moment, it was almost all downhill for Booker. He returned to New Orleans from Europe and found that he couldn't get a gig. Maple Leaf Bar owner John Parsons provided him with about the only steady work he would get for the remainder of his life. For a time, he took a job for the city of New Orleans, sitting at a desk behind a computer in a municipal finance department. A year after his last 1982 recording session (with producer Scott Billington, for Classified), he died, unattended, sitting in a wheelchair in a hallway of Charity Hospital. Though his death was reputedly the result of cocaine abuse, the truth is likely that his body just gave out after years of hard living.Bayou Maharajah could easily have focused on the most sordid aspects of Booker's life. While there is no shortage of mind-boggling detail, first-time filmmaker Keber never leans on it for effect. The movie is emphatically about Booker's music, and you get to hear plenty of it.Most of the interview subjects in the film – most notably Harry Connick, Jr., whose father, for a time New Orleans' district attorney, was exceptionally tight with the musician – are plainly in awe of his work. At one juncture, Connick sits at a piano and picks apart Booker's style, a flexible, wholly original amalgam of classical, R&B, and jazz. But the music resists analysis in the end, and you sit almost stupefied by its brilliance.In all, it's a beautiful picture, and you should – must, actually – keep your eyes open for it. Bayou Maharajah is subtitled The Tragic Genius of James Booker, but the film never wallows in its hero's dark fate. It's a very poised piece of movie-making.

... View MoreThis film sheds some much-needed light on one of the most flamboyant and talented musicians that New Orleans has ever produced. In this nuanced portrayal, documentarian Lily Keber brings to life the little-known (outside of the New Orleans music scene and jazz/blues aficionado circles) legend of James Carroll Booker III. Tragically, Booker was among the best piano players of all time, but was also prone to mental instability and severe substance abuse issues that limited his career trajectory. In addition to paying fitting tribute to Booker's music, what really shines here is Keber's portrayal of his tortured and complicated personality. This is no small feat. Highly recommended.

... View More