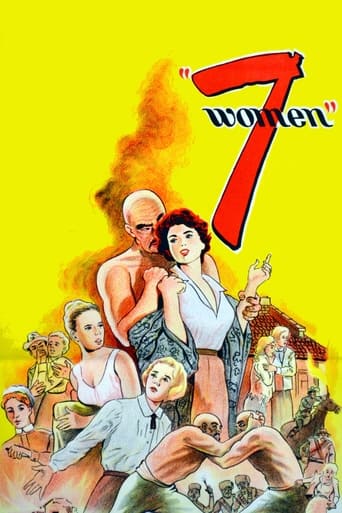

For a film nut like me. 7 Women offers a plethora of pleasures. Patricia Neal was suppose to star but ill health made her unavailable. Anne Bancroft took over as the drinking, smoking, swearing saint. and all the aspects of this complex character are totally real in Anne Bancroft's face. She arrives to the Mission in China like a benevolent tornado. The spectacular Margaret Leighton is the head of the Mission and she plays it like a raw nerve, Among the other women, Flora Robson, Queen Elizabeth to Laurence Olivier's Michael Ingolby in Fire Over England, brings a voice of reason that reassure us, Betty Field , Kim Novak's mother in Picnic, among a gallery of memorable characters, plays the pregnant middle age woman who offends the Christian mission for having had sex with her husband under their roof. Mildred Dunnock, Anna Lee and even Stanley Kubrick's Lolita, Sue Lyon is part of the Mission. On the other side, the villains, that offended so many people, John Ford casts his longtime companion Woody Strode. I understand and even accept all the criticisms listed in the reviews of this pages but, somehow, I can put all that aside and enjoy the plethora of pleasures that it offers.

... View MoreThis isn't so much a review- indeed I didn't know the film existed and I haven't seen it - as a lament for the late Norah Lofts , a writer of great power and subtlety. I can't begin to say how much it looks like Ford mangled her stirring and poignant tale (surely he was the last director on earth who should have been tackling an intricate female-nuanced situation! ) Suffice to say that Loft's Dr Cartwright, far from being some sort of pseudo man-imitating, girl-cowpoke,and American to boot, was actually an Englishwoman of education and compassion, whose outsider status derived from her non-religious stance and relatively 'liberated' attitude to personal freedom. Words fail me as to the ending ......

... View MoreJohn Ford's final film is a real curiosity. Anne Bancroft plays a butch doctor sent to work at a mission in China and ruffles the feathers of most of the missions, especially Margaret Leighton.7 WOMEN is very studio bound and has a real half-hearted feel to it. Bancroft, a last minute replacement for Patricia Neal, is actually TOO strong and her character is really unappealing. Leighton is shrewish and the other women in the classy cast including Flora Robson, Mildred Dunnock and Sue Lyon barely register. And why is 53 year old Betty Field playing a pregnant woman? Her husband is the equally aged Eddie Albert. Mike Mazurki offers a cartoon character version of a savage who invades the mission and puts the disruptive Bancroft in her place. Ford may have viewed himself as a man of the Indians, but he really had no clue of how to handle women!

... View MoreI am still reeling from the powerful ending to this unspoken of movie. John Ford's last entry onto his glittering resumé stuns while it holds your interest at every turn of a scene.It is so hard to resist talking about the ending of this movie. It seethes with so much devastating darkness. And yet, within this darkness, there is a human victory so profoundly complex as to take your breath away in resignation, anger, shock and inevitable acceptance.Anne Bancroft has always been one of my favorite actresses. With all her celebrated roles, I still feel that the depth of talent has never been fully appreciated.Yet, in this role, she displays her talents aplenty.I recommend this seldomly seen movie and I hope it will be brought to VHS or DVD one day so that more will see this movie and its production will not be in vain.

... View More