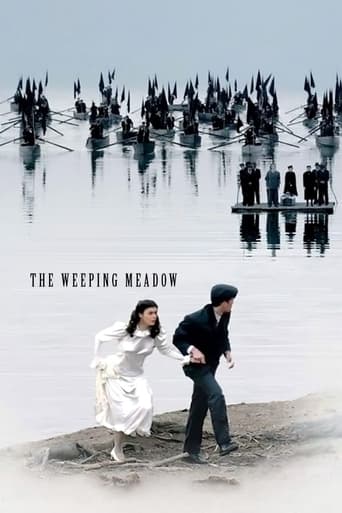

Greek screenwriter, producer and director Theodoros Angelopoulos' twelfth feature film is a Germany-France-Greece-Italy co-production and the first part of a trilogy about the history of Greece, which tells a story set in Northern Greece 1919 where a group of Greek refugees from the Russian harbour Odessa arrives at a place near Thessaloniki. Amongst them is five-year-old Alexis and three-year-old Eleni. Eleni is an orphaned girl who has been raised by Alexis' family, and since childhood they have developed strong bonds to each other. Thirteen years later Eleni gives birth to two twin brothers which she gives away for adoption. Eleni is promised to Alexis' father Spyros, but on the day of her wedding she escapes with Alexis. "The Weeping Meadow" opens with a stellar scene where the viewers are introduced to the main characters. It is told through an emphatic narrative structure and filmed with long takes, diverse perspectives and unusually calm camera movements. Greek filmmaker Theodoros Angelopoulos' subtle filming visualizes his affection for images of people, animals and objects reflected in water. The humane and engaging screenplay with minimal use of dialog written by Theodoros Angelopoulos and screenwriters Tonino Guerra, Petros Markaris and Giorgio Silvagni, tells a story which spans over 30 years and examines themes such as love, grief, immigration, fellowship, melancholy, music, war and hope. The old and accurate costume design and the naturalistic milieu depictions reflects the era it portrays with great conviction in this European art film which contains hauntingly beautiful cinematography by cinematographer Andreas Sinanos, reverent acting performances by the actors who personifies the central characters and scenes of such poetic intensity that it touches one's soul. Watching a Theodoros Angelopoulos film for the first time was reminiscent of the first time watching a film by Andrei Tarkovsky, Andrey Zvyagintsev, Krzysztof Kieslowski and Alexandr Sokurov. His significant individual expression and style of filmmaking aligns him with historic filmmakers like Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni. Most of the acting is interpreted in a low-keyed and internal way which strengthens the effect of the climactic emotional scenes in this quiet and unforgettable movie experience which is filled with an elegiac and longing atmosphere which is increased by composer Eleni Karaindrou's melodic instrumental score. A lyrical artwork directed by a sharp minded visionary.

... View MoreIn some ways, this film takes the best parts of the work of Federico Fellini, Terrence Malick, and Michelangelo Antonioni, and stews them until they melt into a work only Angelopoulos could make. However, what separates Angelopolous films from most other films by even some great filmmakers, is his screenplays. This film was written by him, longtime Fellini collaborator Tonino Guerra, Petros Markaris, and Giorgio Silvagni, and even though- like the other films of his I've seen, this one is spare in dialogue, the story coheres because of the way the scenes are written to allow the actors' expressions convey what words need not. And, like Yasujiro Ozu, Angelopoulos is a master of ellipses- never fully explaining certain things in a film, nor deliberately not showing the viewer things that would be standard in a more linear film. The film's cinematography, by Andreas Sinanos, is spectacular, from the long shots that follow characters from afar, to well-composed foregrounded scenes, to the uses of color throughout. The film starts with muted, almost sepia tones, and grayness, then exhibits flashes of color, here and there, while mostly staying in dark greens, blues, and browns. This heightens the grander moments, such as the bloody death of the musician in the white sheets. The use of water is also wonderful- from the film's reflected shots at the opening, through the constant rains and floods, to the last shots overlooking the water- a far better use of imagery than a similar shot which ends Alexander Sokurov's Russian Ark. In fact, the scenes of the flooded town were a set built in a high, dry portion of Lake Kerkini, which by March, would rise and submerge the set.The musical scoring by Angelopoulos's longtime collaborator, Eleni Karaindrou, is solid, mixing folk songs with classical compositions, all in an understated manner- excepting a great scene where the son auditions with his accordion. Yet, several times in the film, there seems to be an odd noise- like jet sounds in the aural background of some scenes. Is this symbolism or a flaw? Even if a flaw, it is a very minor one, for aside from the aforementioned scenes there are numerous other great scenes in this picaresque film that coheres in the Negatively Capable way John Keats claimed great art works; such as when Nikos dances at night as a saxophone plays, or when Eleni, in fever, babbles on and on of the same things. Yet, at the center of this great film is not only the ellipsis of information, but the ellipsis of self- the exile from everywhere, a theme that defines much of Angelopoulos's work, even if it does not define his art, for that is always on target, and brilliantly wrought. The Weeping Meadow is no exception to that claim.

... View MoreI think anyone familiar with Angelopoulos knows what to expect with his films: long, drawn out, meticulously planned shots that slowly scan environments, with the image composed of not only the foreground but hundreds of yards into the background. I guess some are not impressed with the director's style, but that really astounds me. I definitely see the man as a master of his medium, and The Weeping Meadow is as good as any of his other films every one I've seen so far is a masterpiece or close to it. This film has a lot in common with the director's first big success, The Traveling Players. It follows a little girl, Eleni, from 1919 to the time of the Greek Civil War, at the end of WWII. And, as the title implies, it's a great tragedy. There is a lot of weeping. It may be long and slow, but it's always gripping. Angelopoulos' imagery is second to none in modern cinema. There are just so many jaw-dropping sequences. My favorite was the one where the camera explored its way through a maze of bed sheets drying on clotheslines, discovering various musicians hidden within. It's not a complaint, per se, but if you're going to watch the film beware of its chronological ellipses. The film can skip ahead years in just a second, when the pace usually makes each second feel like years (in a good way!). I hope New Yorker video, or some other company, digs up the Angelopoulos films that have been unavailable so far, and puts The Traveling Players on DVD, as well.

... View MoreHad I known to what I was submitting myself, I would have fled from the theater. The film is dreadful, in the literal sense of the word. Despite striking images, intriguing locales, and a subject matter that might have been fascinating, the film is dead.I was unfamiliar with this period of Greek history, and prepared to experience a great film. The filmmakers's hand is heavy. it is not enough to see a train going by; we must watch it from afar, we must watch it car by car, we must see the smoke, we must see it slow down, and we must see it stop. The director's approach is didactic. Likewise, the characters that he creates never develop, they never change. They are so stereotypic that we wonder, are they meant to be Everyman? Everygirl? Everyoldmusician? Is there some point to this allegory? It is the most pretentious film that I have seen in a long while.

... View More