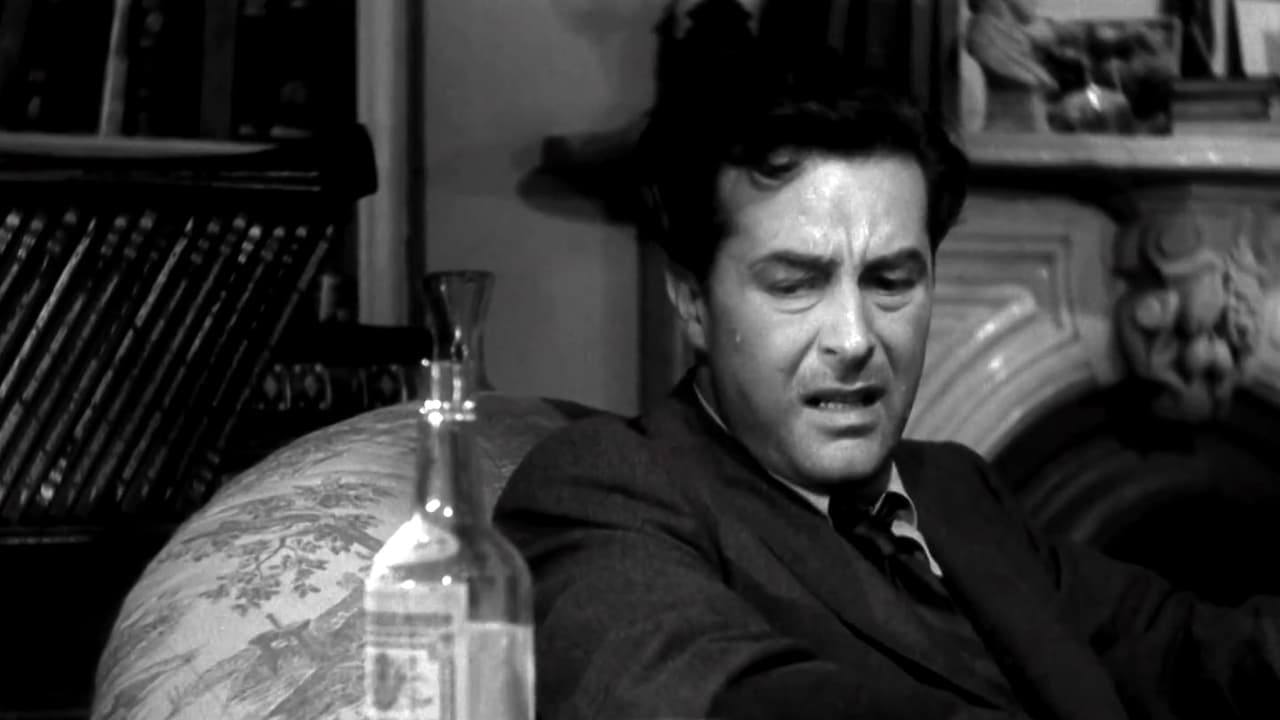

(Flash Reviews)Thrust into a man's mind who is literally perspiring to get a drink. A man so consumed with the thought of drinking or where and when his next drink will come that the whole town, family and friends are aware and either help or reluctantly enable him. He really just wants to be a writer but thoughts of drinking always distract him. The director really gets you into granular details of the desperation this man who is constantly in need of a drink. Details such as seeing liquid ring residue of each shot he's taken at a bar or secret hiding places he hides bottles from his family. It shows the effect on family and friends, not in a preachy way, but very realistic so I tip my hat to the screenplay writers. Looks like this was before AA was a reality...? One of the most intense and gritty tales of an alcoholic I've even seen and this was done in 1945!

... View MoreIn "The Lost Weekend", Ray Milland gave what may have been the screen's first ever serious portrayal of an alcoholic. The dipsomaniac was a stock character of comedy theatre long before films were invented, but Milland's Don Birnam bears no relation to the characters famously played by W.C. Fields.Birnam is a struggling New York writer who gets by with the support of his brother, Wick, and his saintly girlfriend, Helen. These two intend to take Birnam on a weekend vacation that will extend a period of sobriety, however Birnam heads to a bar where he gets drunk and loses track of time, missing the trip. He thereafter heads on a massive bender.There are a series of harrowing scenes that follow, such as the heart-wrenching moment where Birnam is caught trying to steal to pay his bill in a restaurant, and his experience of Delirium Tremens. There is also a sadistic nurse in the real-life Bellvue Hospital where Birnam briefly stays; this was the first movie that the Hospital allowed to be filmed there.The movie has, it must be said, a commendable realism, as does Milland's powerful central performance. The movie even hints at the even more bleak possibility of suicide; however, the ending seems to take a step back from truth, with a happy ending I could have done without.

... View MoreYou'd love to write off The Last Weekend. "Oh, another of those 40s 'social issues' pictures, fraught with contrived scenarios, posturing affectations instead of performances, and a gentle, comforting blanket of artifice throughout." You watch it, and chortle to yourself that it's done well enough for the time, but cute, and showing its age. You, you think, chest puffed, have weathered Requiem for a Dream, Trainspotting, Leaving Las Vegas and more. This quaint 1940s addiction drama won't leave much of a mark on you.You'd love if that were all true.Then it hits you. The film ended 15 minutes ago, and you're still staring down at the floor, in a numb, foggy daze. Every time you close your eyes, you're ravaged by visions of bats crawling out of the walls drooling streaks of blood, or enigmatic, overlapping rings of liquid, like the Olympics emblem turned aquatic pentagram. You hum tunelessly to drown out the frenzied, feral screeches of a sanitarium at night. Your stomach turns at the thought of snapping yourself out of it with a stiff...drink.The high, the haze, of Billy Wilder's masterpiece have worn off. Welcome to the hangover. You let the sordid weight of the picture cascade over you over and over again, like waves dissolving a sandy shoreline to nothingness. You gulp back sin and regret. And, feverishly, you remember. You remember Billy Wilder, coughing up a lung blacker than any noir tryst here. He takes a pot shot towards melodrama and horror movie, and, in the gutter between, hits jackpot. It's a simple story of a simple addiction, taking wonderful, terrible flight in the trace details, with every second shot lined with liquor bottles looming like tombstones, or cascading from the ceiling light fixture like a Bat-signal of blissful betrayal. If you'd gone drink-for-drink with Don Birnham, you muse, you'd have been dead before the first third. And you say a silent prayer for the countless real-life Don Birnhams who have tried and succeeded. You remember that script - too raw, too honest, to not be gutted from the shameful autobiography of its writer, Charles Jackson, who understood the conniving, the ingenuity, the bargaining, bartering, begging, and gamut of lawbreaking rationalized away in the Sisyphean quest for another drink all too well. That pace - creeping indiscernibly from early pleasantries, the eloquent, airy monologues, the guilty laughs, into a steadily tightening vice of claustrophobic, fatalistic despair. The shame of being caught in an unthinkable act, and braying "This isn't me!" more to yourself than your abhorring audience. A lurch all too familiar to those who have added their own barrage of vicious circles to the local watering hole's table top. And that bit where it all goes black, though this sleep has only swirling nightmares to offer. You remember that theremin - more eerie here than any of its usual otherworldly creature feature companions by being as distressingly real as they are reassuringly false. And you remember Ray Milland, all right. Too charming a firebrand not to love, too weaselly, willfully self-destructive not to loathe. He seduces and betrays us and himself over, and over, and over again, and over, and over, and over again we crawl back to him, entranced by his flashing, manic eyes, his glib, sharp tongue, and his crumpling of the deepest ebb of despair. We spare a thought for Jane Wyman, resiliently chipper in the face of a black hole, Philip Terry, charm dulled into flat affect by relentless disappointment, and Howard Da Silva, the warmly roguish angel and devil on the shoulder at once. But it is Milland's ghoulish face, leering like Norman Bates yet pleading like one of his victims, that you fight to expunge from your pounding skull. And is it all a nightmare, to be shaken awake from by a deus-ex-typewriter Hays Code ending as disingenuous as it is jarringly chirpy? Or is this merely another red herring, with another liquor bottle always dangling out the window, or behind the book case, biding their time until the despicably opportune moment presents itself? Only time will tell. But, let's not forget that a circle is the perfect geometric shape. No end. No beginning. One thing is indisputable: whether you bury it fearfully or binge it with the unquenchable ferocity of a Don Birnham, you'll never forget this Lost Weekend. You'll try. But you won't. Delirium is a disease of the night, my friend. Goodnight. -9/10

... View More... and not get tired of it. Ray Milland's performance is riveting and, if you are watching for the first time, the first scene will do nothing but raise questions, getting you involved. How did Don (Ray Milland) get to be such an alcoholic? Why does his brother have a right to say how he lives? What does he do for a living? Why does such a seemingly together woman like Helen (Jane Wyman) stay with this guy for three years? All of these questions get answered slowly as the movie unravels over one long weekend that Don was supposed to spend in the country with his brother, but instead spends alone, but thanks to ten dollars that Don's brother left behind, he does not spend it completely alone - he's got money to buy booze.And yet Don doesn't plan ahead. He thinks enough to cover up the two bottles he buys at the liquor store with some apples that he buys to put up on top of the bag as he walks home so neighbors cannot see the booze, but the urgency doesn't come until he is completely out of liquor and out of the ten bucks to get more. And he is willing to do ANYTHING to get that liquor - he'll pretend to be interested in a girl in a local bar who is obviously crazy about him in order to get a few bucks, he tries to trade his typewriter (he's a failed writer) to a local bar owner for a drink, he steals money from a woman's purse in a nightclub to get booze, he even stages a faux hold-up (he has no gun) to get a bottle from a liquor store.And that's it for the entire movie - Don Birnham and his quest for the next bottle eats all of his time and energy. Other characters are just instruments in that quest or are in the form of flashbacks to tell you how Don got to where he was in the first scene. And then there's that haunting score that runs the length of the film. Everything is brutal realism UNTIL the last scene. Maybe it was the censors, but today it could have cost the film some Oscars.A couple of questions never raised. How did Don's brother Wick manage to support himself AND Don all of these years IN New York City? Didn't Wick ever long for a life and family of his own? There's got to be a limit to anybody's patience and charity, even if they are kin. Another question from an old film buff like me - Isn't it odd how the Great Depression and World War II magically disappear from sight in the past that Don is recollecting. 15 years of American history that effected everybody seems to have no place in Don's story. To look at this film, this shiny bustling post-war world has always been there. This is the turn of film from Depression and world war - collective struggles - back to the struggle of the individual with himself, the beginning of noir.

... View More