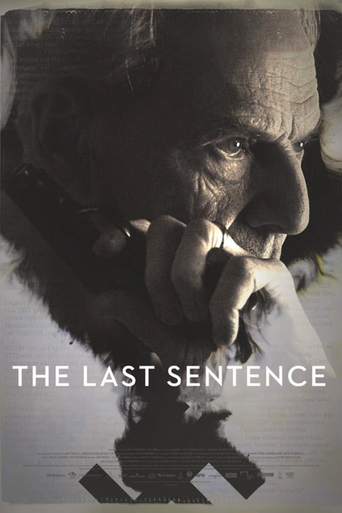

''The Last Sentence'' (original title in Swedish- ''Dom över död man'') is the story of Torgny Segerstedt, a Swedish journalist whose fierce anti-nazi articles became a matter of great concern within the country's political life and stirred major backlash both in Germany and Sweden. The movie begins with Adolph Hitler's rise to absolute power in Germany in mid-1930s and follows the growing aggressiveness and hate-speech of the Third Reich until the ending of the Second World War, examining the influence and effect that the threat of a possible German invasion had on the decision-making of Sweden's government. The film focuses on the much-debated neutrality of Sweden and Segerstedt's bold critique on the inactivity of Swedish politicians even when Nazis invaded the neighboring Scandinavian countries. The basic flaw of ''The Last Sentence'' is that it follows an uneven rhythm and as a result, the movie can be divided into two parts, the first being tedious, almost annoying, while the second picks up speed and leads to an emotionally touching climax. The director, Jan Troell, is one of Sweden's greatest auteurs and each one of his films is characterized by its high-quality standards as well as magnificent performances. In this one, I think that Jesper Christensen's performance deserves to be in the spotlight but the whole of the cast does a tremendous job as well. My rating would be closer to 3,5/5.

... View MoreThe key to this film lies, in part, in understanding the meaning of the title. "The Last Sentence" is an ambiguous translation of the Swedish because a "last sentence" might refer to the last words a man writes. Instead, "sentence" here means the "judgment" one passes on a man who has died--a judgment that endures longer than the judgments that were passed on a man while he was alive.And this citation of the "Hávamál" (an Old Norse 13th-century poem) has a special resonance in light of a toast proposed by Torgny Segerstedt early in the film: Segerstedt remarks something to the effect that we have a sacred duty to tell the truth in public matters, but no such duty in our private affairs.Jan Troell has thus given us a portrait of Torgny Segerstedt as a man who fiercely refused to say anything other than the truth about Hitler and Nazism, but who, at the same time, was incapable of acting in a truthful and caring fashion in his private life--a man who seemingly had a deeper attachment to his dogs than to any of the people who deeply loved him. And Troell has perhaps highlighted the shortcomings in Segerstedt's personal relationships precisely because he wants the viewer to sense this tension in the final judgment we place on the life of a man. Do Segerstedt's attempts to stir the conscience of the Swedes through his writings on the horrors of Nazism cancel out whatever negative judgment we might pass on his conduct as a father, husband or lover? Maybe Troell poses just such a question because he himself may sense that he's nearing the end of his own life. And so what Troell wants, perhaps, is for us to realize that we are all faced with the question of the measure of a person's life and the final judgment to be passed on that life: what weight to give to the life one has lived in public, visible to all, or to the life that one has lived in the shadows (filled with love and affection or not) of one's private life?

... View MoreIt was troubling to view Swedish director Jan Troell's 2012 film based on the experience of crusading journalist Torgny Segerstedt, so soon after the recent tragic assassinations at Charlie Hebdo in Paris. Segerstedt was editor-in-chief of one of Sweden's leading newspapers, and between 1933 when Hitler came to power and his own death in 1945, Segerstedt was a fierce opponent of Naziism, even though much of Sweden's leadership, including the king, was determined to remain neutral and out of the war. The struggle for journalists' right—some would say duty—to speak out despite risks to themselves and others has not ended. Beautifully played by Jesper Christensen, Segerstedt left himself open to criticism and to the devaluing of his motivations by his long affair with a Jewish woman, wife of his publisher. Hollywood's crusading journalists are noble and flawless (think All the President's Men), their presumed moral authority overshadowing any rough spots in their personalities, whereas Segerstedt's uncompromising character is pompous at times and unpleasant at others, he basks in his celebrity, and he's downright cruel to his wife. "Easy to admire, but very hard to like," said RogerEbert.com reviewer Glenn Kenny. Truth told, he loves his dogs best. Producing this film in black and white may have symbolic significance or may be just the preferred Scandinavian style—the film is Swedish, after all. In another Bergman-like touch, Segerstedt sees and converses with the black-clad ghosts of his mother and other women. Slow-moving, like the clear stream (of words?) against which the opening and closing credits appear, there is only a fleeting soundtrack to support the action. The film left me with a lot of unanswered questions. What happened with his writing? When the authorities demanded that a particular edition not be distributed because of its anti-Nazi editorial (which suggests they had imposed some censorship regime), Segerstedt printed it with a big white space where the editorial would have been. Nice. But we never learn whether he was allowed to continue writing after that (or how he was stopped) until a scene that takes place years later. How did the war affect the Swedish people? There's little hint of that, beyond putting up blackout curtains. It seems they had electricity, they had food, petrol, champagne at New Year's. It's primarily the awareness of Nazi behavior that the viewer brings to the film that explains and justifies both Segerstedt's simmering outrage and his country's policy of appeasement. He and his mistress both have suicide plans, if it came to that, but in the absence of any tangible, on-screen threat, their preparations seem self-dramatizing and almost childish. Segerstedt in a sense provides his own epitaph, which is also the Swedish title of the movie—"Judgment on the Dead"— based on a line from a famous Old Norse poem, which says the judgment on the dead is everlasting. History's judgment on Segerstedt would be that he was of course right about the Nazis. And if, as the King believed, it would have been his fault if the Germans invaded the country, he would have been among the first to die. NPR's Ella Taylor called the film "A richly detailed portrait of a great man riddled with flaws and undone by adulation."

... View MoreSwedish cinematographer, screenwriter and director Jan Troell's thirteenth feature film which he co-wrote with Danish screenwriter Klaus Rifbjerg, is based on a biography about Swedish publicist Torgny Segerstedt from 2007 which was written by Swedish writer, actor and director Kenne Fant. It premiered at the 23rd Stockholm International Film Festival in 2012, was shot on location in Luleå, Gothenburg and Stockholm in Sweden and is a Sweden-Norway co-production which was produced by Swedish producer Francy Suntinger. It tells the story about Torgny Segerstedt, an editor-in-chief of a daily newspaper called Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfartstidning who lives in Gothenburg with his wife Puste, their daughter Ingrid and his three dogs. Torgny is a strong opposer of the reigning regime in Germany which is questioned by many and he often attends upper-class parties with Puste who mostly stays in the background and observes him and his lover Maja Forssman.Precisely and brilliantly directed by Swedish filmmaker Jan Troell, this finely tuned biographical story which is narrated from multiple viewpoints though mostly from the main character's point of view, draws a mindful portrayal of a Swedish theologian in his late fifty's and his relationship with his Norwegian wife, a married Jewish woman and his somewhat lonely battle against the German national socialism. While notable for its naturalistic and distinct milieu depictions, distinct black-and-white cinematography by Jan Troell and Swedish cinematographer Mischa Gavrjusjov, production design by Swedish production designers Pernilla Olsson and Peter Bävman, fine costume design by Swedish costume designer Katja Watkins, editing by Jan Troell and film editor Ulrika Rang and use of sound, this character-driven and historic drama depicts a nuanced and involving study of character and contains a great score by Norwegian composer Gaute Storaas.This tangible, romantic, political and conversational tale about a truly dedicated anti-Nazi who some thought would jeopardize the national security of Sweden due to his outspoken publications about Nazism and possibly drag his country into the war, is set in West Sweden before and during the Second World War in the 1930s and early 1940s and is impelled and reinforced by its cogent narrative structure, substantial character development, quick-witted dialog and the remarkable acting performances by Danish actor Jesper Christensen, Swedish actress and director Pernilla August, Swedish actress Ulla Skoog and Swedish actor Björn Granath. A reverent, enigmatic and atmospheric narrative feature which gained, among other awards, the award for Best Director Jan Troell at the 36th Montreal World Film Festival in 2012.

... View More