I've come to think that Ozu is the most original of all directors post silent era. The End of Summer is just another example of how Ozu manages to make a compelling film out of the most mundane of plots. This also one of the funnier Ozu movies. The early scene of Akiko's meeting with a potential suitor is handled with great light comedic touches (the nose signal). Ozu's signatures are all here: the static camera shots,shooting actors from behind, sudden jumps in timeline, and of course great acting. I can't think of a director who is more instantly recognizable not just for technique but also plot and dialogue. There is only one Ozu and this is one of his best, right up there with :Late Spring, Tokyo Story, Early Spring, and Tokyo Twilight

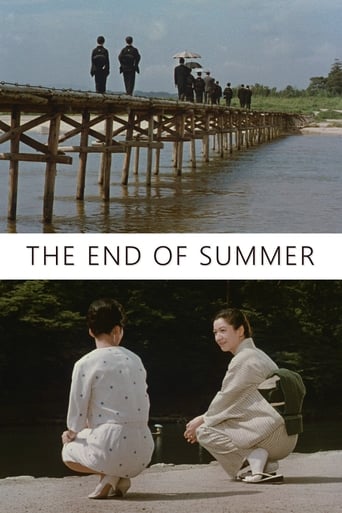

... View MoreThe international translation for Yasujirô Ozu's second last film is usually either Early Autumn or The End of Summer but its original title would actually be "the autumn of Kohayagawa family". Family and its changes were themes that characterized all the films by Ozu; he often portrayed the collision of different generations as well as the change of habitat and family structure. The End of Summer is a story about a family whose company has been manufacturing rice wine for generations. The head of the family is getting older, and therefore moving aside from the business, while the economic competition coerces the family to consider about joining a bigger corporation. This is one symptom of the transition. The other is being fought on a personal level, inside the family.The sisters have their contradictory aspirations and marital worries but, together with their mother, they frown upon their father who, during his later years, visits an old lover of his. During one of his trips, he gets a heart attack; summer ends, both season and generation change. At the father's funeral the visitors cross a bridge to a new era. When the smoke of the older generation rises from the pipe of the crematorium, the new generation continues leading their lives in their own ways. This beautiful poetic sequence relays an emotion of personal loss and the continuous cycle of life -- the sudden beauty and transience of life. During the funeral the true, essential values crystallize as does the inevitability of change. To this nostalgia of the old world Ozu adds a little optimism when the youngest daughter decides to go to seek a path of her own.There is something extremely interesting in the cinematography and use of static camera in the films by Ozu. He often lands the camera down, to the ground. Ground, earth and mud are important for Japanese people and, the first association which this camera work occurs, is the fact that Japanese people eat on the floor. But it's also an ideological choice; looking at the world from the perspective of a child. It's a moral approach which becomes an aesthetic fact, and it adds deep meaning and a lot of heart to this beautiful film. However, it's not just the cinematography in the visual aesthetics that captivate us but the use of colors, and the precise consideration of 'mise-en-scene'. I am on the verge of sinking to an aesthetic tumult while admiring the world of colors in The End of Summer, the exotic colors that are strange and unfamiliar to us occidentals. These kind of warm and touching films about family, Ozu made during his entire career. In addition to this particular intimate family story, the film talks more widely about cultural transition, and in its visual aesthetics Japanese tradition meets western popular culture: advertisements, neon lights and cultural behavior of the west infiltrate to the Japanese landscape. Traditional outfits turn into western clothes and the children try to attain independent solutions, on their own, without consulting their parents who they've seen as their masters for decades. Coca-cola, baseball and American soldiers tell about globalization and this vast cultural transition, which is inevitable. In the midst of depicting this harsh transition Ozu achieves to keep his heart-warming tolerance -- he never points the finger at us -- but also his bitter and intelligent irony.

... View MoreOzu's penultimate film is also one of his best. As in many of his movies, the theme here deals with the dynamics of a traditional Japanese family. The aging patriarch of a family has to deal with marrying his two grown daughters (one is divorced with child, the great Setsuko Hara), the financial problems facing his small sake producing business, the reunion with his long lost lover and their capricious daughter and, last but not least, his impending death. The death theme hangs throughout the movie; Ozu was probably thinking of his own death when he filmed this (he would live only a couple of years more); the last shot has black crows standing over the patriarch's gravestone. Ozu's films in color are even better than those in black and white: his famous sense of composition shines even better. Besides, I love color films from the late 1950s and early 1960s period, perhaps because they show us what society look like before the great disruption of the late 60s (this is not personal nostalgia, since I wasn't even born then). Overall, one of Ozu's best films.

... View MoreAfter his second experience with colour, a light, happy "Ohayo", secretly epic and impressed, Ozu shot one of the milestones of his career: "Kohayagawa-ke no aki" is in my recollection, with "Banshun" and "Munakata shimai", his best work. Most of the themes exposed in previous films (father's intervention in his daughters' lifes, love (in the hands of others), solitude) are here integrated in a comedy-structured film that becomes a drama. It's perhaps his unique melodrama and it is shown with the desperate of the last breath for some characters, as usual in Ozu, doubtful and seeking a place for their quiet happiness.There is no Ozu film nearest Sirk's or Minneli's universe like this one.

... View More