Film director Stephen Kijak's film is to be commended for never descending into minutia on Engel's life. In fact, virtually nothing, after the initial information on Engle's youth, is mentioned of his private life. This is refreshing, for it lifts the film well above any claims of being a vanity documentary. The negative is that Engel's 'art' is simply not good. Yes, he had a deep, powerful bass voice, and it was put to great effect in the early recordings. But, listening to his latest efforts, not only are his lyrics bad (Jim Morrison, Walker is not, even as some talking heads bizarrely link him to T.S. Eliot, Samuel Beckett, and James Joyce)- in a jumbled sense, but they border on PC and the 'music,' such as it is, is random and found noise, not harmonies and melodies. To top it off, Engel's voice is a dim echo of its former glory, often descending into what seems like a parody of some local 1960s television station's late night horror film show host's attempt at singing to a bad B film.Initially, the film plays out like a mockumentary, but the infusion of vintage television clips dashes that surmise. What is not dashed is the reality of how limited the 'art' of Engel's music. Great art does art well. Visionary art pushes boundaries, as well. But, to push the boundaries back, the artist has to stay anchored to the extremes, at least of the art form. In the case of music, this means non-banal lyrics, damning predictable percussion, varying melodies and other such extensions. Simply going off into a corner and wailing, or grunting, is not an extension of music nor singing, as arts. Of course, that is hyperbole, but Walker's latest efforts smack of a phenomenon known in the arts- that of the spent artist realizing he'll never duplicate his earlier successes, so he just preens and deranges, then hides behind the veneer of his earlier success, as a 'genius,' or the like (and it's no shock to know Engel worships the Beatniks). Engel simply never expands the boundaries of music- pop nor otherwise, even as talking heads damn many of the progressive rock acts of the 1970s that went far beyond Walker's experimentalism: Yes, King Crimson, and others.Scott Walker: 30 Century Man (the title taken from an Engel song) is a well wrought and exquisitely structured film on an ultimately interesting subject, but that subject is not Engel nor music nor art, but the peregrinations of the spent artist in search of that golden nipple needed to nurse him into senescence's uneasy drool. Now, if only director Kijack can find an artist and subject worthy of his talents, the film will be a landmark in the genre.

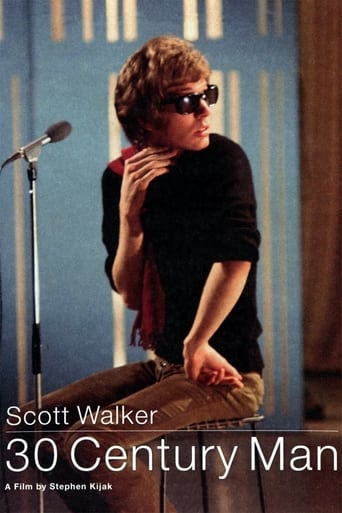

... View MoreMore than five years in the making, filmmaker Stephen Kijak gave us a chance to spend some time with Scott Walker, or Noel Scott Engel (his real name if you prefer), and listen to other collaborators and musicians who have been touched by Scott, talking and commenting while listening to selections of Scott's music presented during interviews. Scott, the consummate and committed songwriter-poet-explorer of the 'un-tread' territories of the senses, intrepidly transforms his internal imagery and inherent clues into his unique music, 'avant-garde' or otherwise (as demonstrated in his albums "TILT" 1995 Fontana Records UK, and "THE DRIFT" 2006 4AD label).From the beginning of the reel, we can tell he's a soft-spoken man, an ordinary looking man (regular guy) now in his sixties (he was quite a heart-throb, in his curly pop hairdo and husky low tone with his guitar, being the lead singer of the famed Walker Brothers circa 1964-66). He's not flashy or arrogant (as you might think pop culture idols would be), actually he's downright shy, sort of hiding away under his baseball cap. Once you hear him speak, passionately about his music, offering amusing anecdotes of 'yesteryears', you will be absorbed into this world of Scott Walker and wanting to know as much as you can about him, go checking on the Web for his music, album availability, even his song lyrics, without hesitation. (There's a substantial database of lyrics site at "scottlyrics.vniversum.com/".) Amazon.com seem to have a comprehensive source for all Scott Walker's albums, from Scott '1' (the Jacques Brel period), Scott 2, 3, 4, "Tilt" and "The Drift", including "Nite Flights" 1978 - the one-time reunited Walker Brothers album (MP3 album 'downloadable'), more Scott solo efforts like "Climate of Hunter" 1984, "Pola X" 1999 film soundtrack of nonconforming French director Leos Carax, "And Who Shall Go to the Ball? And What Shall Go to the Ball?" 2007 orchestral piece in four movements by 4AD label.He is, indeed, a 30 Century Man, a poetic purist at heart. His meticulous care in composing guitar chords for his songs as composer Hector Zazou pointed out as he wondered how Scott had in-tune and out-of-tune chord arrangements at the same time - true genius recognition, alright. Collaborating arranger & keyboard player Brian Gascoigne explained how Scott went for the unconventional - the in between 'chord' and 'dis-chord' and holding for 16 bars. It's amazing just 'soaking up' the many shared accounts described by Scott's fellow musicians, colleagues, and managers. "His lyrics are peerless," so Brian Eno admirably confirmed. David Bowie is executive producer to this documentary film of Scott Walker, who is definitely still alive and well, seriously flourishing in the music world in UK, where he's fondly appreciated more.Considering most of the films and documentaries of the decade are about musicians past, like "Control" (2007) on Ian Curtis of Joy Division, "A Skin Too Few: The Days of Nick Drake" (2000), both died quite young at 24 and 26, Kijak's documentary "Scott Walker: 30 Century Man" is invariably of a different tone, definitely worth your while especially if you appreciate music or film-making, as you'll get to enjoy sight and sound simultaneously (there are plenty of typographic visual play on the presentation of Scott's song lyrics through out the film). This is a gem well-cut. Enjoy the 95 minutes and you shall rewind to review, if it's certain segments to repeat, or simply the whole length of the feature once again.Memorable quotes: It's fascinating hearing him talking about his songwriting that "it has to come to you, can't push it". And what a sensible man Scott Walker is as he said, "I'll know when I write my next record where I'll be".

... View MoreWhen one of my musical heroes, Julian Cope, mentioned Scott Walker as one of his big influences, I had to listen for myself. I found the "Scott 2" CD by chance in a cutout bin and have been hooked ever since. The arrangements, lyrics, emotional punch and sheer weirdness of songs like "Plastic Palace People" and "The Amorous Humphrey Plugg" are impossible to get out of your mind once you've heard them. And then there's Walker's baritone voice. I can't think of anyone else singing these kind of songs and not making them sound ridiculous or pretentious. I've since acquired more of his solo work and have found it, by turns, equally fantastic and puzzling. This film does a good job of showing the arc of how he went from pop crooner to enigmatic experimentalist. I was pleasantly surprised when Walker took off the baseball cap and began to take us through his musical history. I had been afraid of him being cold and distant, given his disdain for publicity. Instead he seems to be a decent enough fellow, who just happens to possess a talent for displaying his inner demons effectively. While watching, I began to realize that the intent of his work has not changed over the years, it has merely become starker in conveying Walker's dark, though human, vision. In showing the recording process (one musician punching rhythms on a slab of meat) and hearing him explain the inspiration of certain songs (like the chilling footage from post-fascist Italy), the film gave me more insight, and respect, for Walker's later works like "Tilt" and "The Drift." If anyone wants a glimpse into a TRULY creative mind, whether a fan of Walker's music or not, I recommend they see this film.

... View MoreScott Walker is an American composer and poet (original name Noel Scott Engel) who has lived in England for many years. Originally he was a handsome Sixties pop star who sang with the group The Walker Brothers in a "warm, sepulchral baritone" (as Eddie Cockrell puts it in 'Variety') that made young girls scream and, in England, was more popular than the Beatles. After a couple of albums the group disbanded (though reuniting for a while in the Seventies), and Scott went solo. Gradually over many years, moving haltingly at first from covers of other people's songs to increasingly complex and personal compositions in albums a decade apart, Walker has established a reputation as a unique musical figure focused on recording, not public performance, which the screaming girls taught him to hate. His haunting, surreal, emotionally demanding pieces, all the way back to the Sixties, have influenced Radiohead and The Cocteau Twins. Vocally admired by Sting, Brian Eno, and David Bowie (executive producer here), he receives on screen testimonials from Ute Lemper, Jarvis Cocker, Lulu, Marc Almond, Damon Albarn, Allison Goldfrapp, and Gavin Friday.Kijak's film is interesting enough to attract new converts to this cult artist. It's also a pleasure to watch because it's so well made. It's convincing, elegant, revealing, seamless, and frequently quite beautiful.The film begins by teasing viewers with the historically reclusive nature of the man ever since he gave up public performance some time in the Seventies. Then it springs its bombshell: Scott has consented to a lengthy interview for the film. '30 Century Man' is not so much a life as a life-in-art. We learn little about personal matters such as depression and a drinking problem but everything about his style and imagination and the stories of the individual albums. The beauty of the film is as a portrait of musical evolution describing changing ensembles, recording methods, and moods from album to album, the latest many years apart. It's also the story of an artist influencing other artists, rather than prancing before the public.Before we get to that, there's enough footage of TV performances to show that The Walker Brothers (who were neither brothers nor named Walker) were a conventional cute singing package. M.O.R. slop, you might say, especially considering their peak year of 1965 was the time when Dylan released 'Highway 61 Revisited.' On his own, Scott wanted to do Jacques Brel, the angst-ridden, sweaty French songwriter. He did Brel smoothly, in English, with that mellifluous baritone of his.Later when the solo compositions emerge, he moves further and further toward art compositions with horror-show moodiness and highly crafted sound landscapes. The latest songs some say are not songs at all but something else, haunting tone poems with words born, Scott says, out of a life of bad dreams. Some of the images used to illustrate later compositions, however, still put one in a Seventies mood, though the dreamy floating patterns, colors, and texts have nothing dated about them. Maybe even the mature Scott Walker style grows out of a strain of Seventies English rock impressionism. (That may partly explain Walker's remaining in the UK, but he was also in love with Europe through its films.) The lyrics, often floated dreamily on screen with lines in space, are occasionally quite strange.One suave passage traces key songs from all Walker's albums through time to show he did interesting work even early in his solo career. While the music is playing multiple screens show musicians listening and commenting on the work.Though the film doesn't say so, Walker's lyrics from the Eighties on, when the albums became less frequent, are stronger and freer.'Cripple fingers hit the muezzin yells/some had Columbine some had specks/Cripple fingers hit the rounds of shells/some had clinging vine some had specksThe good news you cannot refuse/The bad news is there is no news' ('Patriot,' a single, 1995)Excerpts we hear (and partly see) show Walker is adventurous and extravagant (but a deft and calmly focused director) in studio orchestrations, using lots of strings and building a large wooden box to get just the right percussion sound. Another time a percussionist must hit a large slab of meat. Doing the music for Leos Carax's film 'Pola X,' he has a large studio full of loud percussionists. Classical musicians are instructed to play violins to imitate the sound of German planes coming in to bomb English towns--not an easy day's work. It's all very intriguing, suggesting a personal musical world that's scary, but still welcomes you to come in.

... View More