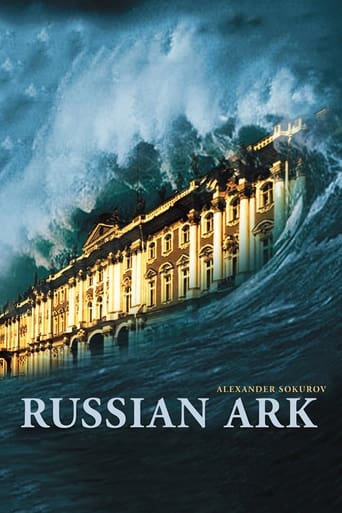

There come times when I am seeing a film that announces and declares itself as a piece of magnificent, magnifonic, exceptional and daring work of art that I have to reckon with the objective vs the subjective perspectives: it's one thing to recognize how brilliantly a film is executed as opposed to how I felt about the content, or, in the old Ebert philosophy, not what it's about but how it's about it. Because objectively speaking, I'd find it hard to argue or hear a persuasive argument to the contrary that this is the highest orchestral arrangement of cinema that is possible.By that statement I mean that you can't watch this and not be impressed on some level - this is one of a small handful of feature films (which originated with Hitchcock's Rope and became Oscar fodder in the best possible way with Birdman) that are shot in one long, unbroken take, and because it was shot in digital format and not film the director and cinematographer, Alexander Sokurov and Tilman Büttner respectively, could arrange it so there were no cuts (unlike that pussy-footin' Birdman, psshaw, having seamless edits, the nerve!) And it's not simply in the cinematographic prowess, it's much in the way that a director of live TV has balls of steel: orchestrating and conducting everyone, like a symphony, to be on just the right marks at just the right beats - and this is a cast that features hundreds, if not over a thousand, people - and it goes through different lighting set-ups and costume changes and the lead actor Sergey Dreyden (kind of a Russian Peter Cushing with his black attire and hard cheeks and nose) has to carry it in large part emotionally speaking, or at least on some intellectual level.So for arranging everything and getting it to move together seamlessly it's a real *achievement*. But is it a great movie aside from that, or even a good one? In some part it is wonderful, in large parts, but (and I have to put the 'but' in there), it's hard to sometimes be completely engaged with material that is so experimental. For me I actually discovered not too long into the film I was locked in more with the audio side than even the visual side. Not that large parts of this aren't visually arresting - it can't not be at certain times if only because of the paintings on display (it's a lot like being on a class trip, so if you don't enjoy going to a museum, frankly you may not enjoy chunks of this picture very much) - but it's how the filmmakers uses audio, and remember this IS an audio-visual medium, that gives Russian Ark its fullest impact.What is the focus of the film for example? Is this a documentary? A dream? A schizophrenic time travel trip that's like if you took Tarkovsky and mixed him with Doctor Who (all in Russia, of course)? Well, let's look at the 'voice' behind the camera, the man who seems to be following our "Stranger" in black who wanders through the hallways and the rooms full of paintings and the corridors and then... finds himself in an opera, a giant ballroom with hundreds dancing in unison and soldiers marching and then Catherine the Great pops up. And all the while this voice that accompanies this man, is it a person there, or is it a ghost? I found it difficult to parse at times if there was a figure actually there - not just the main character but others who pop up from time to time - acknowledge 'his' presence. But is he or 'it' there? Maybe it doesn't matter in the way that the ambiguity adds to the mystery of it all. The whole experience, as the director's attempt to go for the Orson Welles quote to the max - "A film is never really good unless the camera is an eye in the head of a poet" - has the feeling of a dream-documentary, if that makes sense, like we're wandering around some Hyper-Intellectual who has doused himself in the kerosene of Russian art and history (or also European history, note the mentions of German artists and composers and others) and is wandering around the halls and ballrooms and devastation and joy of centuries of work. While it's not really *all* the history (not enough Kossack blood or Bolsheviks me thinks), it's an engaging look at many of the key portions of how iconography, both in style and in artistic expression, come to the foray.Or... something like that. It could all be an extravagant d***-waving measure, like "look at what *I* can do with my digital camera and a whole army of people to command!" - but then isn't that what most cinema is all about? There are stretches that, even at 99 minutes, start to drag, but this may also be a first-timer reaction. I'd like to revisit this in a few years or so, or perhaps sooner, and see how, not unlike if I saw a series of paintings as I traipsed around a museum, my reaction would change.

... View MoreA film in one take! Of course let's not forget Murnau and "The Last Laugh" made 75 years before. It is a technical feat to be sure but it runs out of steam not too long into the film. We figure the trick out early on and visually, the film just seems to ramble. It feels at times like a guided tour of a huge museum where there so much great art the mind simply turns off. Trying to fit a plot of sorts into such a project is hard enough as it is, but an uninteresting story line... I enjoy long takes - please don't get me wrong on that issue - but we have been spoiled by some virtuoso directors who can use them and cut brilliantly as well. Bravo for the technique but one viewing was more than enough.Curtis Stotlar

... View MoreI just love this movie. It is something that is not every one will understand nor appreciate. From the get go from the begging when you - the 3 person - arrives with the three friends you are taken for a ride through the Hermitage in Russia. I could not take my eyes off the screen since I felt like I was waiting what was around the next corner and what other marvels will I see. The costumes are fantastic and the acting superb. But you know what it seems like if you were a quasi-ghost of some sort so that you can travel around without the everyone seeing you, and when those that do you are just another person in the act. Pay attention to the last shot, it sums up the reason why what you just experienced was the say that you did.See it with an open mind and you will "sail away".

... View MoreSokurov's Russian Ark is a magnificent exhibition of pre-Soviet Russian high-culture, presented in a wandering and dreamlike single shot from a first-person point of view. The underlying plot is mysterious – two ghostlike figures, a 20th century Russian, and a 19th century European of Dickensian appearance – roam between rooms in the Winter palace, viewing and sometimes participating in a variety of historical events. Sokurov drifts between exhibit, theater, and reality as easily as between eras of Russian history. Actors sometimes portray actors and sometimes portray historical figures, and the aloof European companion treats the historical events the two men visit with the same academic reverence with which he treats museum exhibits. With hundreds of actors in magnificent period clothing, historical events reenacted, and stunning works of art and architecture admired and discussed, the film is a moving work of art that manages to appreciate and interpret itself. The strange European companion, who mocks and chastises Russia for its tyranny, its obstinacy, and its adoption of European culture, nonetheless revels in the aristocratic opulence of the Winter Palace and the grandeur of the historical events they attend, sometimes with religious awe, sometimes with childlike playfulness. The quiet Russian narrator is generally defensive, quietly prideful of Russia's past and persistence, but humble regarding its challenges. Always, the division between Russia and Europe is insisted, although the interchangeability of the two cultures pre-revolution is obvious. There is hidden in this film a thesis of some sort, that when Russia left the Tsar it also left Europe. In one scene, Stalinist-era museum curators worry about the state's neglect of the Winter Palace and Russian history, saying "It will be their doom if the tree falls, there will be nothing left." Sokurov seems to argue that despite the detached opulence of the past, the accomplishments of the Imperial era are of undeniable importance to the survival of Russian culture. The uncertainty of the Nation's future is an obvious concern; when the narrator is asked whether Russia is a republic in the post-Soviet era, he responds with "I don't know." In the final scene, the narrator leaves a magnificently extravagant Imperial ball, saying "Farewell, Europe," to his companion, and stepping out into a stormy and misty sea. Russian Ark is beautiful, illogical, sometimes creepy and sometimes playful, and can be viewed as both a historical exhibit and a commentary on the past and future of Russian culture.

... View More