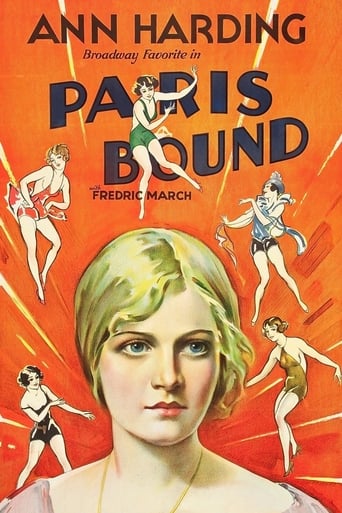

The rediscovered Paris Bound is, as other reviewers have pointed out, something of a disappointment. It might be considered the quintessential talkie in that the characters talk and talk and talk and talk and, frankly, not to much purpose. Philip Barry had a certain reputation as playwright and Paris Bound had a certain success on the stage because it treated a subject that was still regarded as extremely risqué in the US but it is an absolutely dire piece of work. Passages quoted in other reviews give a good idea how "precious" and artificial the dialogue is and comments in other reviews also reveal how ambiguous the treatment is. The fault again lies largely in US society which required such controversial subjects to be couched in fatuous double-talk and to be presented in a totally misleading fashion.So the controversial nature of the play/film is all a matter of trompe l'oeil. The "liberal" couple are not very liberal at all (even at the outset) but quite extraordinarily uxorious, so that, in a play/film supposedly about adultery, we have in fact an abundance of passionate husband-wife kissing and precious little adultery (talk figures strongly there too) and the conclusion is of course deeply conservative. Adultery, it would seem, is just an illusion; blink twice and it just goes away. The husband's divorced parents (arguably the genuine liberals) are treated rather as aberrant monsters.Barry shows essentially the same ambiguity in The Philadelphia Story which similarly toys with ideas of divorce and adultery, to end with a predictably conservative conclusion. Divorce, like adultery, is also apparently an illusion. Laugh twice and that goes away too. The Philadelphia Story is also extremely talkative but has the distinct advantage of being funny which Paris Bound is most certainly not.Virtually the only "American" film-makers who manged to break through this "no sex please, this is the USA" barrier, were Erich von Stroheim and Ernest Lubitsch. Stroheim capitalised on his established wartime reputation as a "German villain" to get away with things(possible because they were heavily marked "villain") which no other director in the US could get away with. Lubitsch, after long years of producing light comedy and musicals to establish a huge if slightly bogus reputation, and by dint of a good deal of skillful mise en scène and a certain low cunning,was able to produce a remarkable film like Design for Living and make light of adultery in A Certain Feeling or To Be or Not To Be. But these remained the exceptions that proved the rule.The Stroheim logic was peculiar to his own situation and rather ingenious. When a character has been shown, with official approval, raping a nurse and defenestrating a baby in a propaganda film, it is a bit difficult to find grounds on which to then censor the deviant behaviour of a succession of rather similar characters played by the selfsame actor in his fiction films (Blind Husbands or Foolish Wives or Blind Husbands)But even so Stroheim had to fight hard to maintain his independence and had plenty of problems with censorship, particularly on the part of the snip-happy producers who would eventually succeed in destroying his directing career completely. He was after all at the time only the best director that the US had ever produced (by quite a margin). Who needs such people? Gloria Swanson was probably right in thinking that even Stroheim would not have got away with Queen Kelly as originally filmed - the later scenes, cut from the version eventually shown, are still quite troubling to watch even today. She is wrong in blaming (as she later did) the Hays Code, which did not then exist but, contrary to popular belief, there was plenty of pre-code censorship and the Hays Code merely "codified" rules that very largely already existed.The difference between "pre-code" and "post-code" is for the most part just wishful thinking. Most censorship, before and afterwards, was in any case, as with Queen Kelly, self-censorship by the producers, constantly terrified of any kind of controversy, which, in those days, still had the power to ruin careers and conceivably even institutions. The Hays Code (in any case their own creation) simply gave producers a convenient alibi. So it is not really the case that the Code prevented directors from doing this, that or the other (particularly the other) but rather that it gave carte blanche to the producers and their henchmen (the so-called "editors", but sometimes more accurately described, even in credits, as "cutters") to chop the films about so as to render them "harmless" in the way they were so fond of doing.The "Lubitsch touch" was, in the end, a more sustainable method of getting round the rules than "the man you love to hate" method, especially as it was a myth originally created by the production companies themselves. Lubitsch simply broadened the definition. To return to this film, Fredric March is adequate (the least talkative character, he doesn't really have much to do but kiss) and Ann Harding is, as ever, dazzling, but her two other films made in the year, Her Private Affair - attacked, ironically, by reviewers at that address as being based on a "failed" play - and Condemned are both better films than Paris Bound although this was the film that made Harding a star because of the rather spurious reputation achieved by the play.

... View MoreSlow and stilted, this film is obviously the adaptation of a play--all the action takes place (or could) in one room. The director shows his tin ear (and whatever is the visual equivalent) by starting the movie with Ann Harding and Fredric March going through the wedding service, which goes on and on and on. The two attractive leads, both highly accomplished actors, are the reason for seeing this, as are such distinctly period touches as his saying to her "Take a deep breath" and handing her a cigarette. Ilka Chase also makes two brief, welcome appearances as a fashionable, flippant socialite. But the plot is minuscule and is also well past its use-by date--we're told that a good wife overlooks a husband's affairs if he really loves her and the other women mean nothing to him. And how does she know he feels that way? Because he says so!

... View MoreThe movie begins with the wedding of Mary (Ann Harding) and Jim (Fredric March). They will be a quite happy couple. Their wedding vows are terribly solemn. It turns out that that dedication won't be the only reason for their bliss.After the ceremony, the couple's female 'friend,' Noel, is distraught because she will never give up pining for Jim. Jim reluctantly obliges Mary's request that he try to assuage Noel before they alight on their honeymoon. It appears second nature for Mary to consider another woman's feelings at a time when she could be feeling the euphoria of marrying the man she treasures. The woman Mary sends Jim off to comfort is not a retiring flower. Noel revels in self-pity over her unrequited love, telling Jim, 'I know you kiss me every time you see me what does it matter if you haven't done it as long as you're thinking of it? You can't be indifferent to me so don't try.' Later, Mary tells Noel that she and Jim both love Noel. That is the thing about Mary – she has the right touch. She had the wisdom to send Jim to Noel to try to calm her and the kindness to try to make Noel feel loved. Mary intends to be wise about her marriage, too. She and Jim are very wrapped up in each other. How desperately they want to be a 'success.' They must mingle with people often so that they won't long for some experience beyond each other: Mary: I don't like monopolies, at least not for you and me. Jim: Okay, but I'll like you best.The point is not to let other people become novelties (temptations). Richard admires Mary from afar. She once spent much time listening to and composing music with him. She tries to make him feel comfortable with her new status, calling herself an old married woman and telling him that she expects that he visit her and work in her new music room.Mary determines to be self-disciplined each year as publisher Jim goes to Paris to meet authors. She never goes with him. 'What about my child?' is one of her excuses. But she can hardly bear even to see Jim off at the ship so much does his absence hurt her. 'Heavens yes,' she would like to go with him, but 'I have the notion that married people need a holiday from each other.' So as for spending six weeks in Paris with him she says, 'I just never do.' Mary is filled with exemplary traits: She has the charm of being well-spoken. To 'How's your baby?' she quips, 'Come out tomorrow and I'll hold a one man exhibit.' And no one could be more discreet. When her friend asks her why she didn't come to visit when she was with Jim in Paris the previous year, Mary realizes that she has been mistaken for the 'other woman' Jim was really with, and calmly replies, 'It was the shortest kind of a trip.'One is left to wonder if the thesis of the film is that infidelity doesn't matter because in truth it doesn't even matter to the person committing it. A wanderer is compelled by physical stirrings beyond his or her control almost as if s/he were an innocent bystander to chemistry.Two scenes in the film bring this theme to light. Jim's divorced parents have a curious conversation:Father: You made a failure of your marriage. I may have committed infidelity but you committed divorce. You did me out of my marriage and home. You destroyed a spiritual relationship that belonged only to us. Jim is a lot like me. Mother: Then I pity Mary.The father repeats this line of reasoning when Mary discovers that Jim may have been unfaithful.Mary: I don't feel compelled to share him. Father: What has this one misstep got to do with you? I doubt if you've shared anything. Mary: I'm insulted. He couldn't love me and go with her.Has Mary never had any 'stirrings' for anyone else in all the years she has been married to Jim? Never, she says. He wishes she had so that she would know it's possible.Richard is writing the music for a ballet. He can't finish it. Mary tells him he'll never finish anything. Richard believes that the unfinished ballet represents Mary's unfulfilled relationship with him. She never finishes anything either, i.e. her self-discipline toward her marriage leads her to repress her feelings.Is the film trying to say not only that such attractions are inevitable but that acting on them may also be unavoidable at times? Because, you see, the next thing Mary knows, she has had a minor indiscretion of her own.Father's point seems to be that chemical attraction is a small thing that one is powerless to control and that when one acts on it, one is not sharing anything that is really of value to one's spouse. Perhaps Mary's experience with Richard teaches her this.Mary tries to be honest with Jim:Jim: I'm not certain I want to hear it. I'm certain I don't want to hear it. I don't ever want to hear any bad news.He suspects Mary wants to tell him of her weak moment with Richard. He knows only that he wants to keep alive the truly affectionate love they have shared. He has no double standard. In rejecting this 'news,' Jim is not only excusing his own actions but excusing Mary's transgressions, if she has made any.Neither lets pride destroy the unique romantic married relationship they have. Spontaneously, they set off at 2 a.m. to see their little son. Jim loves to see him when he's asleep.Jim: Have you forgotten anything? Mary: Only my dignity. Jim: That's not anything.

... View MoreDated, stagey and suffering from a static camera, this early Philip Barry play still manages to pack a wallop due to Barry's wonderful dialogue and the strengths of the leads, Frederick March and Ann Harding, right at the beginning of their careers, but possessed of a naturalness that carries this movie along. Thanks to the Vitaphone Project for reuniting the rediscovered soundtrack to the moving image.

... View More