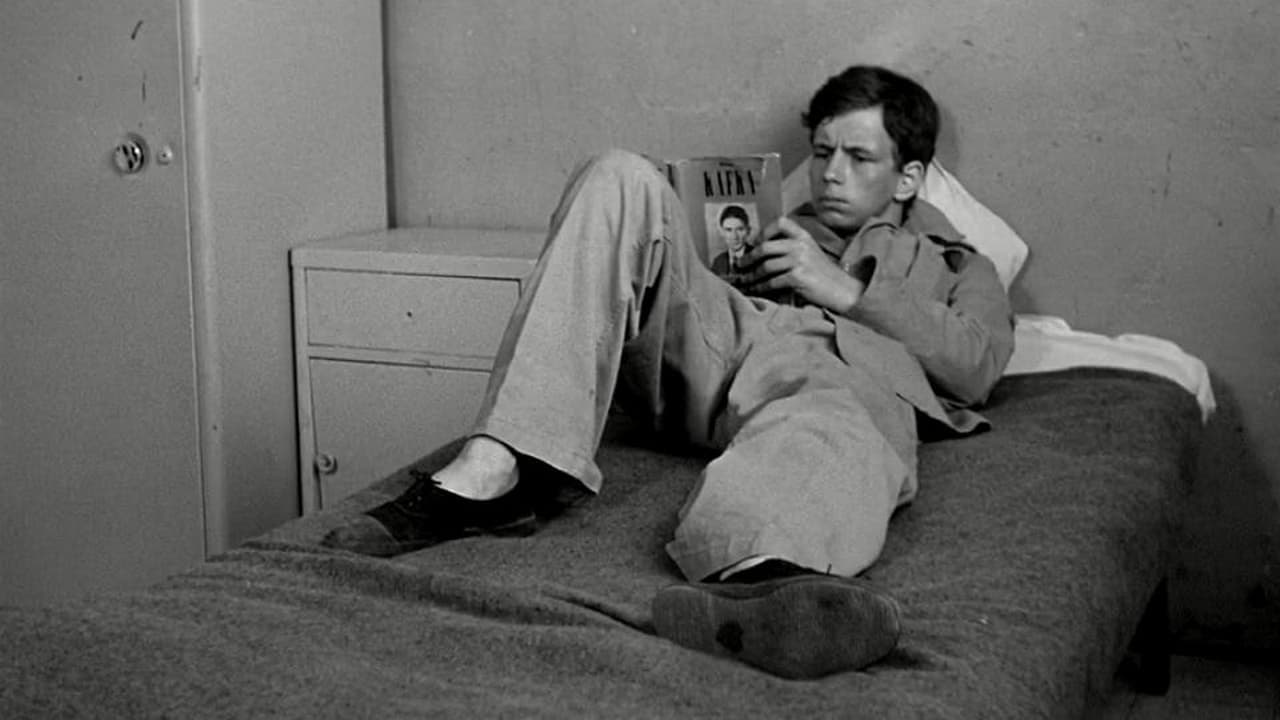

Bill Douglas directs "My Childhood", "My Ain Folk" and "My Way Home", a trilogy of films which charter the life of Jaime (Stephen Archibald), a young boy living in 1940s Scotland. Based on the director's own experiences, the series watches as Jaime is subjected to a series of misfortunes and abuses, most of which take place in the small mining village of Newcraighall.The trilogy is structured as a series of loosely repeated cycles, Jaime struggling to cope with parents, grandparents, surrogate parents, half-brothers and surrogate brothers. While Jaime remains locked in limbo, adults come and go, either dying, committing suicide, abandoning him or being consigned to mental wards. Douglas fancied himself as a class conscious artist, a "socialist realist", but unlike most neorealist works, which sanctify the poor and downtrodden, his trilogy pushes past canned sorrow and proletariat piety and instead tries to tap into a kind of nauseating self-hate. Everyone here is cauldron of seething resent, long resigned to a life of dishing out and receiving emotional and physical abuse. Meanwhile, Jaime begins to plot his escape.And so Jaime hitches a ride on a coal train, befriends a German POW and falls in love with the idea of becoming an artist. This is where the trilogy gets problematic. It is not only that Douglas has a narrow view of the working classes, but that in tracing Jaime's rise out of the slums (via his meeting the educated middle class, the elite upper class and the development of a love for art) the trilogy begins to exhibit a somewhat snobbish attitude and dismissive stance toward whence Jaime came."My Childhood" and "My Ain Folk" are the best films of the trilogy. "My Way Home's" narrative has been criticised for its "confusing" structure and Douglas' refusal to explain major plot points, but such an initially jarring approach works well upon re-watches. The trilogy ends powerfully with the sound of what seems to be gunfire and explosions played over the glorious image of a tree, the juxtaposition epitomising the twin poles of Jaime's uncertain future. "My Ain Folk" opens spectacularly with the glorious, triumphant image (taken from "Lassie"?) of a dog scaling a majestic mountain. This image – the allure of cinema and the hope of escape – then snap-cuts to grim, black-and-white Scotland.The trilogy's narrative, which focuses solely on suffering townsfolk, is as depressing as Douglas' aesthetic. Shot in black-and-white, the series stresses doom and gloom. Respite is infrequent. Douglas uses long periods of silence, slow camera work (and much locked down, static shots) and moments of eerie, discordant sounds, to create a unique aesthetic. The trilogy's disturbing tone – autobiography meets creep-show horror – strongly resembles Lynch's "Eraserhead".The film represents another link in the spreading chain that is neorealism. Very loosely speaking, neorealism began in Italy in the 40s, spread to France (cinema-verite) in the 50s, to Britain in the late 50s and 60s ("Kitchen sink"), to the United States in the 60s and 70s, Scotland in the 70s and Iran in the 70s and 80s. The style is a delayed reaction to the socio-political-economic situations in these respective countries.Douglas' filmography is revered in Scotland, Wales and Britain, but none of his films were widely distributed or have been widely seen. Because of this, they've developed a somewhat overinflated reputation.7.9/10 – Makes a good companion piece to Satyajit Ray's Apu trilogy ("Song of the Little Road", "The Unvanquished", "The World of Apu") and Truffaut's Antoine Doinel series ("400 Blows", "Stollen Kisses", "Bed and Board", "Love on the Run"), all autobiographical films chartering the transition of young boys into adulthood. Worth one viewing.

... View More'My Way Home' is the last of three autobiographical films written and directed by Bill Douglas, recounting his childhood, adolescence and early manhood. Although I never met Douglas, I was present for a couple of hours during a location shoot (near Cerne Abbas, Dorset) for his best and most elaborate film 'Comrades', the story of the Tolpuddle Martyrs. I stood just outside the sight-lines, watching Douglas direct the camera and hearing him motivate the actors. He was a unique and distinctive artist; I regret that he died so soon and that he didn't make more films.In all three instalments of Bill Douglas's autobiographical trilogy, the protagonist -- ostensibly Douglas's alter ego -- is cried Jamie. The name change warns us that some fictionalisation is in the works, but we're never told precisely at which points in the story, nor how extensively. The most famous case of this sort of substitution would be the example of Francois Truffaut and his cinematic alter ego Antoine Doinel. I suspect that Jamie conforms more closely to Bill Douglas's life than Doinel to Truffaut's.SPOILERS AHEAD. As the third film begins, Jame's mother and grandmother (who raised him) are dead. Jamie was the product of a tryst with a local man; we never learn if it was a one-off or an ongoing relationship. At all events, Jamie's biological father (well-played by Paul Kermack in all three instalments) did very little for him in his formative years (as we saw in the first two films). Now, belatedly, he actually makes some attempt to take Jamie into his home ... to the consternation of his wife and their son, who is older than Jamie.Some of the early sequences here take place in an orphanage. I was deeply impressed by the performance of Gerald James as Bridge, the governor of the orphanage. He expertly conveys genuine compassion for each of the children in his charge. It's Christmas Day in the orphanage, and Bridge plays Father Christmas by leaving a wee prezzy in every bairn's stocking. But he mustn't favour any child over any other, so he gives each boy and girl the same present: a harmonica! The image (and sound) of several dozen children all simultaneously blaring into harmonicas is astonishing. In front of each child is a clootie dumpling: I never saw so many interchangeable dumplings in identical clooties.I found myself speculating about what Dennis Potter would have done with this material: the orphans become a chorus line of harmonica virtuosi (led by Larry Adler), accompanied by tap-dancing clooties.In the first two instalments of this trilogy, Douglas mostly avoids arty-farty compositions. Here, we encounter a shot of a dozing alderman that seems a bit too self-conscious. I rumbled he's an alderman from his chain of office.In Jamie's adolescence -- purportedly Bill Douglas's own adolescence -- he feels artistic urges. Jamie says that he wants to be a painter, which of course everyone interprets to mean a house-painter. When his semi-foster family twig that he wants to paint poncy portraits, we get the usual kitchen-sink dialogue about the need to 'get some dirt on yer hands' and such like.Jamie ends up in a three-shilling doss house run by the Salvation Army, which is a step up from his previous experiences.Now there comes a sudden lurch to a desert landscape, which turns out to be Egypt. Annoyingly, we hear Jamie's voice-over while the camera moves BACKWARD through this sterile land. It turns out that Jamie has joined the Army, but there's no real explanation. Was he conscripted? Is this his National Service? Most likely, he simply enlisted because he had no better prospects ... but I was irritated that Douglas didn't see fit to explain this crucial transition more clearly.Apparently, the late Bill Douglas had some of his own most formative experiences as a young man in the British Army, stationed in Egypt. I'm told that the single most important personal relationship of Douglas's life transpired with one of his squaddies in Egypt; after they were demobbed, they came back to England together and set up housekeeping. None of that is conveyed here. This third instalment of Douglas's trilogy shows signs of laziness: he bungs various events into this movie because they were part of his life, and are therefore important to him personally ... but he fails to give them the dramatic weight or the narrative significance to make the audience care about them. I found 'My Way Home' very much less compelling than the two previous instalments of this trilogy, and I'll rate it only 4 out of 10.

... View MoreI'd never heard of this or the first two parts ("My Childhood" and "My Ain Folk") of the trilogy it concludes. I wonder why, because taken together they seemed to me one of the best films I'd ever seen--the more so that they're not the type of film I usually seek out or enjoy. Even while watching them, I kept intending to switch them off, but they were so good, I couldn't. At first they looked like nothing new: in style and technique (e.g. the deliberately reflective pace of the editing), they very much resemble low-budget art films circa 1960. And I couldn't always figure out what was going on--which relatives lived where, or how the character got to where he was. Even the final panning shot of this film, though I ran it a couple of times over, I don't understand; it seemed right, I just didn't know exactly what I was supposed to be looking at. But against all of this was the almost painful clarity and believability of the work as a whole. It has no dramatic structure to rely on, and really no need of it, because all of it clearly derives from the structure of the creator's own life. Only someone who had experienced it and remembered how the experience looked and felt could have re-created it so vividly: sliding down the slag heap, sitting watching grandmother in her chair, careering up the stairs of the boarding school, each detail of each vignette. It struck me especially that although the child is as mute as children usually are in art films, he isn't the under-characterized, under-feeling icon child characters are generally made into; he's a child who would be (and probably was) mute, but he seems real. And unlike most victims in films, who are usually pawns in the conveying of some political message or simple sentiment, he's shown as actually living his life, even at the worst, e.g. when, and after, he's severely beaten. The tale is told in vignettes, but they make up the impression of a life, not a synthetic melodrama. One detail I found interesting is the absence--one might almost conclude, the stunting--of any sexual interest; at one point the boy stares at a woman's legs, but almost at once--and significantly, I think--he raises his eyes to her unhappy face, which is turned away from him; the only gentleness, and almost the only human contact, he meets with, he gets from two men who both seem to be understood as homosexual, though no special emphasis is attached to this; it's just one detail of many, all intense with meaning, all of interest: e.g. the landscapes of the desperately poor mining neighborhood having almost the look of a fantastic realm, like something out of Mervyn Peake--as a child would see them; and the grandmother in all her contrary, incomprehensible moods--again, as they impress a child. We all forget, we stop seeing and feeling, we put the unassimilable complexities as far away from us as we can, because they keep us the children who have no power of them; but this director hadn't forgotten, he'd clung to them, and labored, obviously, to knead them together into this great, triune film. It's one of those I can well understand other people's disliking or dismissing, but after which dislike or dismissal I wouldn't be discussing films with them any more; I'd feel I owed that much loyalty to a work like this for what it gives.

... View More