101 years after the release of this masterpiece.D.W. Griffith, the father of film technique decided to make this movie after the Most famous movie The Birth of a Nation (1915), because he was hurt being criticized as a racist. Intolerance was made on a huge budget, breaking the record budget of his previous film. This record remained for almost 40 years. Such huge was the set decoration and art work.Intolerance is an anthology that says 4 different stories in different era. The film is still relevant. Even after a century of the film's release, the time passes but the situation is same "Intolerance", one form or the other, it still exists. Suffering never ended.A definitely must watch for all film lovers. Do not miss it. #KiduMovie

... View MoreIt surprises me that "Intolerance" was such a box office bomb when it first came out back 1916. Sure, it was especially complicated and hard to follow for the time, but the sheer spectacle of it feels like it would not only really attract audiences of that time, but even our time. The battle sequences are so exciting and suspenseful that it's hard not to love their intensity and well crafted nature."Intolerance" doesn't follow one simple narrative, but four narratives, each narrative from a separate time period, from the Babylonian era to modern day America. Instead of, more conventionally, presenting each story one at a time, D.W. Griffith cuts from one story/time period to another in an extremely influential way. It's clear that this makes the film horribly complicated for a 1916 audience. Heck, today the film still is pretty complicated!Many people may say that the film is a bit melodramatic or-*GASP*-dated, but, to be honest, it's a film made 100 years ago! And, even if it is a bit corny at times today, there still is a lot of stuff in "Intolerance" that is still truly emotional and gripping to this very day.If you hate "The Birth of a Nation", you still may love "Intolerance". It has the technical mastery of "The Birth of a Nation", but without the blatant and repulsive racism. So, if you feel like you should never give Mr. Griffith's work a chance after a film like "BOAN", please rethink your decision, because you sure will be missing out on an epic masterpiece!

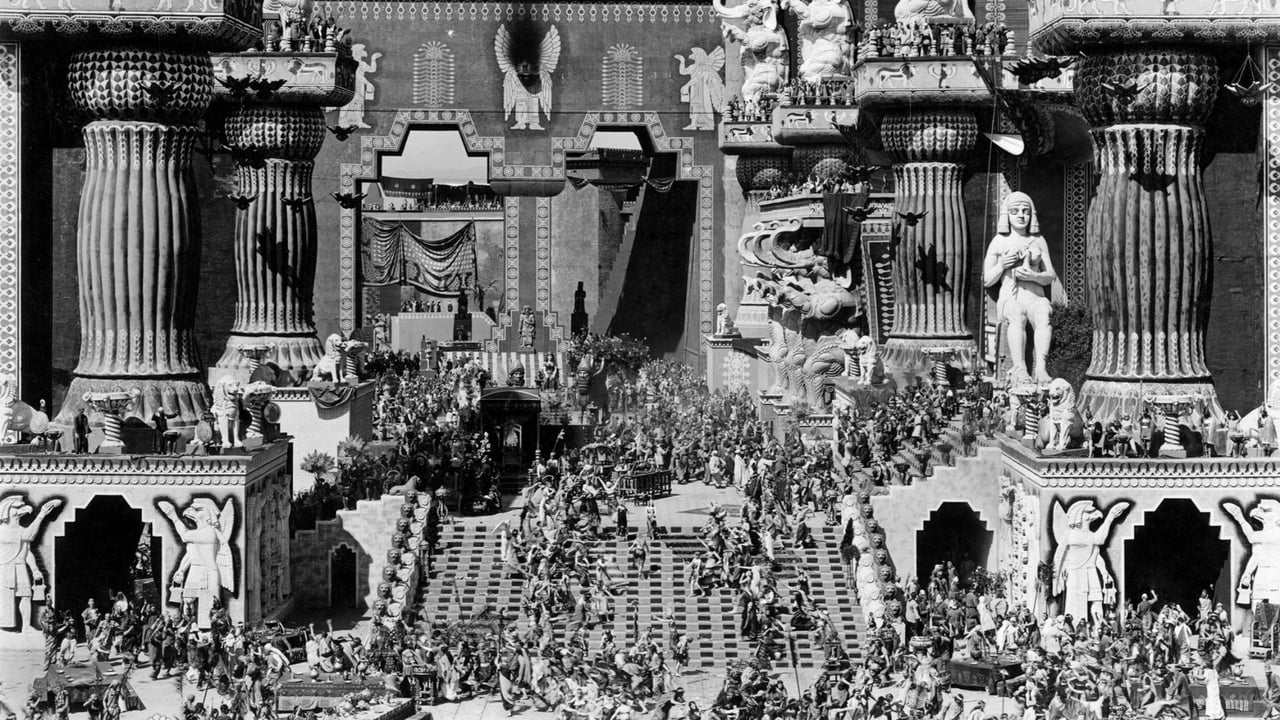

... View MoreThere's a misconception surrounding INTOLERANCE, which states that DW Griffith made this movie in order to retract or apologize for the racism in BIRTH OF A NATION. This is not the case; in fact, much of the driving concept behind INTOLERANCE is Griffith's desire to assert his freedom of speech. Griffith tells four separate stories, at different points in man's history, that deal with the consequences of intolerance and repression. Here's my review.SCRIPT: The modern story (set in 1916 in a nameless American city) is by far the most emotionally involving. It revolves around the plight of a young mother whose baby is taken by interfering reformers, and her husband who is unjustly accused of murder. The Babylon story shows a rather tenuous grasp of history, affirming that treachery and religious intolerance was the reason for Babylon's downfall; however, it does present us with the Mountain Girl, who could rightly be called the first female action hero. The Christ story is really just used as kind of a commentary on what's happening in the previous two stories, using the apocryphal account which states "Let he who is without sin cast the first stone" (actually, this wasn't in the original writings), and the Huguenot story of religious persecution isn't really developed enough to be interesting, at least from what surviving footage we have (difficult to judge since there are so many versions available.) His grasp on what actually constitutes intolerance is rather shaky, affirming that intolerance is the reason for the troubles of the Dear One and the Boy in the modern story. Still, one central story would have allowed Griffith to more clearly develop his ideas – but juggling four at one time with this strained idea of intolerance results in something of a jumble. SCORE: 5.5/10 ACTING: There are at least three standout performances here. Constance Talmadge is wonderful as the Mountain Girl – charismatic, comedic, and lots of fun. Miriam Cooper delivers a soulful and restrained, modern performance as the Friendless One in the modern story, and Robert Harron is compelling in an understated way as the Boy, very naturalistic and expressive. Mae Marsh's performance as the Dear One was a mixed bag to me. Her incessant hypercaffeinated jumping around in the first part of the modern story got on my nerves (although this is likely Griffith's fault – Mary Pickford states that Griffith liked his heroines to behave this way and Pickford refused to do so). Once her character matures and settles down, though, her performance improves notably – her eyes are particularly demonstrative and vivid. As for other performers, Margery Wilson shows potential as Brown Eyes but doesn't get much of a chance to make an impression, and much of the acting in the historical segments falls into the stagy, overly emphatic style of the time. And there's A LOT of that, unfortunately. SCORE: 9 for Talmadge, Harron and Cooper, 7 for Mae Marsh, Margery Wilson, and the people in the modern story, and about 4 for everyone else. 6.5/10 CINEMATOGRAPHY/PRODUCTION: This is where the movie excels. There are some revolutionary shots and techniques here, most notably in the Babylon story, with the famous shot that descends upon the gate of Babylon. Visually, the film is marvelous, with tracking and panning, shots, close ups, and abundant use of tinting (of course, this depends on which print you watch. I watched the Kino version, which is available on Netflix's streaming service). The sets in the Babylon story are massive and exquisitely well photographed. You get bird's eye views of the scenery of Babylon, exciting shots in the modern story with the car chasing the train, and some beautifully illustrated title cards. Griffith's command of editing and cinematography compensate somewhat for the ideological weaknesses of the script. SCORE: 10/10 SUMMARY: INTOLERANCE is a very mixed bag. It does have fascinating moments and stunning cinematography and production. Some of the performances are outstanding, and some are rather dated. However, it does have historical inaccuracies. Perhaps its greatest flaw is that it ultimately bites off more than it can chew and doesn't really make its case against intolerance as strongly as it hopes because its concept of intolerance is very vague. It's also VERY long and probably more for film buffs than casual viewers. It has great moments, but perhaps just as many not-so-great ones. SCORE: 7/10

... View MoreHave you ever been intolerant? Felt intolerance for the very notion of someone being intolerant? Wondered if tolerating the intolerance of another makes you intolerant (or tolerant)? Ever wondered why a reviewer would repeat one word (in different forms) so often? I'm just taking my cues from D.W. Griffith's ancient epic follow-up to the staggeringly racist Birth Of A Nation. You get only 1 guess at the film's title.Four separate story lines connecting the theme of intolerance are threaded throughout the movie, from the Jesus story to a modern (in 1916) story about a young woman and her beloved man who is facing a harsh sentence at the hands of the authorities. Curiously, the Jesus story is the one that's glossed over. The oldest part of the film would be the sequences set in Babylon, which feature epic filmmaking at its silent best.The American Film Institute had Birth Of A Nation on its 1998 Top 100 list, but they knocked it off the 2007 edition and essentially replaced it with Intolerance, which was not on the '98 list. It's a questionable move because, despite Intolerance's obvious theme of acceptance for all and Birth Of A Nation's blatant racism, Birth is a better movie.That's not to say there aren't SOME treasures in Griffith's second-most celebrated work. He revolutionized the medium over the course of these 2 pictures. Too bad he had to beat the "intolerance" theme on the head so badly. You don't need 3 hours to tell people they should be more accepting of each other. It hurts your movie when you seem to be protesting too much. You can argue this is an important movie. That doesn't make it a good one.If you got something out of this snapshot review, check out the website I share with my wife (www.top100project.com) and go to the "Podcasts" section for our 23-minute Intolerance 'cast...and many others. Or look for us on Itunes under "The Top 100 Project".

... View More