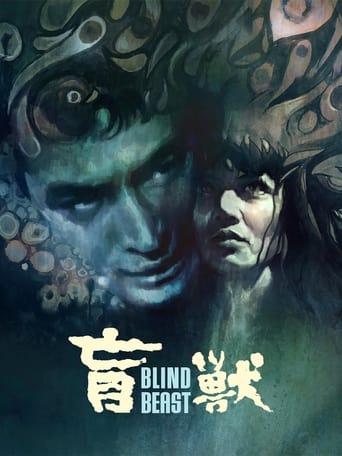

A blind sculptor Michio is fascinated by a beautiful body of a young model. On feeling a sculpture depicting her, he resolves to kidnap her with the assistance of his mother and imprison her in order to create a new type of sculpting relying only on touch. He succeeds in fulfilling his desire. Initially, the model is terrified and does not want to cooperate with the blind man. Notwithstanding, upon seeing his desperation, she agrees to stay, become his inspiration and even a lover so as to be capable of manipulating him and arranging her getaway.Blind Beast (1969) is frequently ranked among the most disturbing flicks ever made which should not be astonishing. This is not only one of the most twisted films ever produced, but also one of the most bizarre works. The story tackles such issues as unbridled human sexuality and obsessive love which leads to sadomasochism, thus to self-destruction. The script could be spoilt in hands of an untalented filmmaker, but not in Masumura's, the director of masterful Red Angel (1966), it is polished to perfection. Masumura, despite his tendency of compounding violence in his movies in order to render tackled problems even more visible, is aware of the screenplay's perversity and is generally interested in exploring the subject instead of shocking. While some scenes might be made in a repugnant way, Masumura executes them totally bloodlessly and evades gore. Hence mise-en-scène is quite subtle and the ensuing waves of cruelty just implied, not explicitly exposed. However, this is not the only reason why the direction is so brilliant. With this flick Masumura proves that he is an extraordinarily imaginative artist. The scenography of the Michio's studio is ravishingly bewildering and mesmeric. To the walls are attached sculptures of various parts of female body – ears, breasts, eyes, noses, mouths, legs and arms which seem to be omnipresent. In addition to this, there are two huge, artificial figures of a naked man and woman. All this gives this location, in which practically the whole story takes place, an extremely outlandish, ghoulish appearance and an unpleasantly claustrophobic climax. Another aspect that makes the content more oneiric is the narration of the model who recounts those events from the perspective of time. It is also remarkable how Masumura's picture keeps one's attention to the very end, despite such an ascetic, staid action and only three characters at director's disposal.The cast is quite decent, although it lacks any famous names to boast about. Eiji Funakoshi is pretty good as the sculptor, even though he seems to overact at times which isn't very disturbing though and these moments are few and far between. Mako Midori is very good as the charming model and probably gives the most impressive performance. Noriko Sengoku as the mother rather stays in the background, since her character is not that significant and feels more like a directional device to fill some plot holes and push the story further. Hikaru Hayashi's soundtrack mostly consists of some non-musical sounds in order to render the atmosphere more wicked and sleazy, while the minimalistic main theme is certainly pretty.It is difficult to recommend it to anyone. This is rather a movie to watch alone. It will certainly leave more sensitive viewers exhausted and possibly disgusted. Nonetheless everyone is likely to agree with the statement that it is a one-of-a-kind flick, regardless of the fact whether one has enjoyed it or not. With regard to open-minded cinephiles, this will be an unforgettable ride. As far as I am concerned, it is an audacious work of art that successfully reveals all darker aspects of human sexuality and should be hailed for its eminent uniqueness.

... View MoreI was in the same boat as I'm guessing most of the people reading this are; how shocking can a movie from the 60's be? Very shocking, is what I'd say in regards to Blind Beast.The plot for the majority of the film involves a blind sculptor kidnapping a young model, and locking her in his weird studio. The model then spends most of the remainder of the film trying to get out, in different ways. Then, for some reason, the last twenty minutes are almost completely different to the rest of the film, turning way more art-house and also more exploitative, disturbing, and even bordering on pinku.What stands about Blind Beast is how proficient the whole thing looks. Other then one or two things (such as small televisions), Blind Beast could be released now and it would still look modern. The studio room where most of the film takes place is amazing, with the walls obscured with life-size stone limbs and other giant body parts, and the two behemothic sculptures in the centre of the room. The acting is also very good, especially the blind guy.I went into Blind Beast not knowing what to expect, and came out pleasantly surprised. It succeeds as a stylish but creepy and ultimately freaky Japenese film, and did it all without a lot of nudity or blood.7/10

... View MoreMy response to this movie is a little different than others I've read. Many point to themes like sadomasochism, the cruelty of art, and addiction. However, no one seems to have noted the rather obvious moral. In fact, the movie constantly tells viewers how to interpret its symbolism. Far from subtle, it bludgeons us with the desired interpretation with the same force Michio uses to drive his sculptor's knife through his model's limbs. It is a cautionary coming-of-age tale that enacts a distinctly Japanese version of the Oedipal myth in which the son must overcome his mother rather than his father (there are no fathers here).The blind Michio is incomplete. As the model Aki tells him, he is not a real man but a momma's boy, a child who still sleeps with his mother (which he does). His mother has done everything in her power to preserve Michio's infantile dependence. She helped him build the cavernous warehouse and fill it with the grotesquely bizarre sculptures of female body parts. The model Aki quickly realizes these are just more symbols of Michio's infantilism. Michio reacts with stunned recognition when Aki points out to him that he has made the figures so large because they represent his childish perspective. To a certain extent, Aki lessens Michio's blindness by repeatedly opening his eyes to the reality of his situation.Aki's mother, on the other hand, will go to any lengths to preserve Michio's blind reliance on her. She is more than willing to participate in kidnapping and perhaps worse to provide him a new plaything. Indeed, without this accomplice, Michio could never have captured or held Aki. After Michio has chloroformed Aki, his mother leads the way back to the den and guards the door to prevent Aki's escape. However, when Aki starts to become more than a toy to Michio by awakening his romantic and sexual desires, she threatens the mother's dominance.Again, Aki offers the interpretation of what must follow. She promises to have sex with Michio, even marry him, but only if he will break totally with his mother. In effect, she tells him that to become a man he must reject his mother and assert his mature sexuality with her. She adds that any good (Japanese?) mother would welcome such a change in her son. This sets up a literal tug of war between Aki and the mother for Michio's affection. The seductive Aki stands on one side of Michio exhorting him to choose her in return for her sexual favors, and the mother pulls at him from the other side, warning Michio that Aki is a lying slut who will betray him. The symbolic psychological triangle was so explicitly rendered that I couldn't help but laugh out loud as Michio repeatedly knocks his mother to the floor during this struggle. Then the mother pulls out the big guns, reminding Michio of all her sacrifices in bearing, birthing, and raising him. But Michio fires back with the ultimate guilt trip, accusing his mother of being the cause of his blindness. With one final shove, Michio ends his psychological struggle by knocking his mother against a pillar, after which she dies from the blow to her head.Michio has literally and figuratively broken the triangle and started on the path to manhood by choosing Aki and an adult sexual relationship. But he doesn't stop there. With the mother no longer blocking the door, Aki believes she can now escape her blind captor. She bolts, but Michio intercepts her. No longer needing his mother to control Aki's feminine assertiveness, Michio drags Aki back into the sculpture gallery and rapes her on top of the gigantic nude sculpture. Earlier, Michio had asked Aki why she agreed to pose nude for a photographer but refused to allow him to feel her body so he could sculpt it. She replied that the photographer was a famous and respected artist who presented her in a way she wanted to be viewed, as the image of the "new woman." In fact, the photographs depicted her in various states of naked bondage. Michio now explicitly forces Aki to accept the traditional role of women in Japanese culture that the photographer only symbolically portrayed -- as an utterly submissive sex object.Interestingly, it is only when Michio begins to physically abuse Aki that the director Masumura allows the viewer to enjoy Aki's full sexuality, exposing her breasts for the first time in live action (they were also visible at the beginning of the movie in the portraits exhibited by the photographer, another "real" man). Once violently subjugated, the formerly willful Aki not only accepts the submissive role but embraces it to such an extreme that she adopts Michio's disability, becoming blind herself and symbolically accepting his view of the world. She encourages him to beat and mutilate her, and she ultimately allows him to objectify her totally by dismembering her. She becomes like the sculpted body parts that adorn Michio's world, another product of his artistic vision.With Aki dead, Michio also commits suicide and validates his mother's warning. The mother had cautioned that Michio did not know the real world. Once Michio leaves the safety of her symbolic womb for the path to manhood, his end is inevitable. Maturity ultimately means death. So we're left with a very transparent rendering of a basic maturation myth with some peculiarly Japanese elements. To become a man, a boy must reject his umbilical dependence on women and take on the dominant role. Independent women, on the other hand, are seductive charlatans (except for you, Mom). To be proper members of society, they must submit totally to the desires of men. And of course, sex, as always, equals death for both, but neither has any choice but to accept it as an inevitable consequence of growing up. Obviously, Blind Beast is a feminist's allegorical nightmare. Nevertheless, it is a fascinating rendering of an archetypal story.

... View MoreA tortured blind sculptor kidnaps a beautiful female model and forces her to pose for the perfect sculpture. Even though this film only has a few characters in a couple settings, it has some very fascinating and unsettling set designs. The room where the sculptor works on his art is impressive, to say the least. As for the subject matter, I was surprised at how much ahead of its time it was. My only problem with the film is that the few characters in it aren't fleshed out enough. This makes some of the character transitions seem unbelievable or even goofy at times. So perhaps it could have been a bit longer with better characterization. Otherwise, this is a good, original, and shocking dramatic horror.

... View More